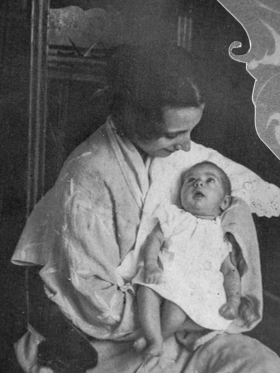

I was born in

Berlin in Germany in 1922.

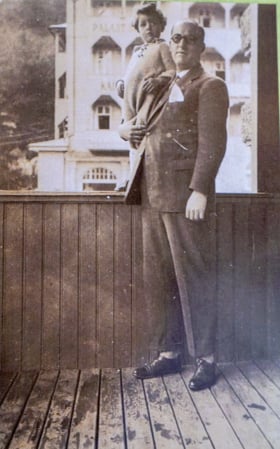

I remember

standing on a balcony...

Where was I in Berlin?

I was looking up and the zeppelin went by.

You know, memories going by like that.

I was always sitting in the

in the last row

I was drawing and I don't know what else,

but I wasn’t listening very much.

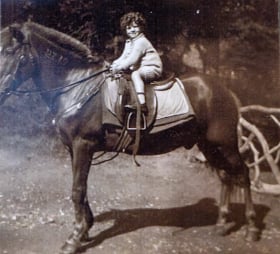

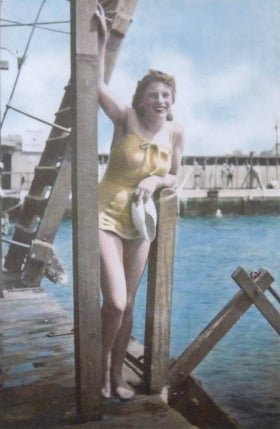

I was good at the rings.

Gymnastics, yes.

I loved my ice skating.

Yes, and winter

and the tennis courts...

They make them freeze over.

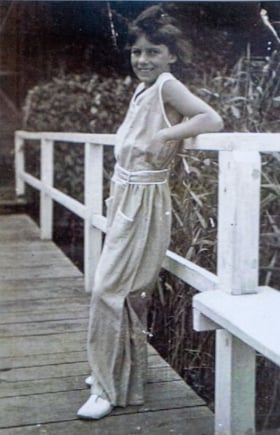

I remember I used to be in movies,

in silent movies.

So then they asked me,

what language did you speak?

I remember

sitting up on a sort of a balcony.

My mother gave me morning tea

and the extras were all standing down

there looking up

and envying

me for I was

eating things

and they didn't have anything to eat.

The memories that come back in pieces,

you know,

one minute

they're there and then they’ve gone.

My father used to take me to the museum

every Sunday morning.

And he always made me

look at one painting at a time.

And I never got through all of them.

I think that he took me

so I could remember them.

Before we left Berlin,

we went to Kempinski

and we had our last meal in Berlin

at Kempinski.

I had my gramophone with me

when they asked me at the border.

“Why did you...?” I said, “Well,

they're always giving me parties

when I go there

and so now I'm going to give them a party.

That's why I’ve got the

gramophone with me”.

Overnight we went

to Holland

and we stayed with my cousin in Zandvoort.

We were waiting there to see whether

we would be able to come to America,

I think, or to Australia,

and Australia came first.

My mother’s cousin was here.

My father, Adolph,

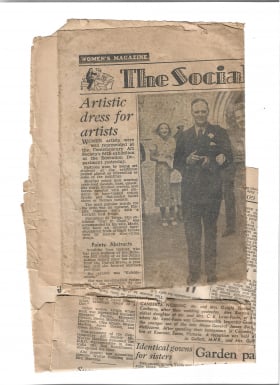

Adolph, had a fashion [business].

He was quite well known.

My mother was in the hat business,

my mother was a milliner,

but she only learnt millinery

when we went out [from Europe].

You know, she had to learn something.

She didn't make them herself.

I think she had people make them for her.

She used to make hats for Lady Gowrie,

the Governor's wife.

At one stage my mother apprenticed me

to a milliner.

I hated it, so in order to get out of it,

I screwed up every hat or whatever I made

until they threw me out.

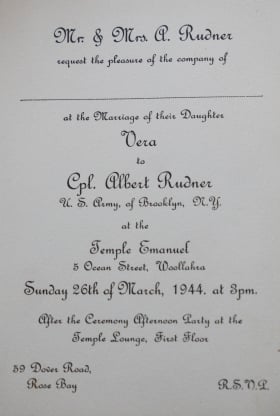

Well, he came up to...

my mother at the millinery business.

And my mother opened the door

and he said that

“My name is Rudner”,

and she said, “Yes, that's my name”.

He says, “No, my name is Rudner”.

Anyway, that’s how it started.

And Rabbi Schenk was supposed to be the...

What do you call it?

But I don’t know, he was interstate

so I had Rabbi Hirschberg

at the Temple Emanual.

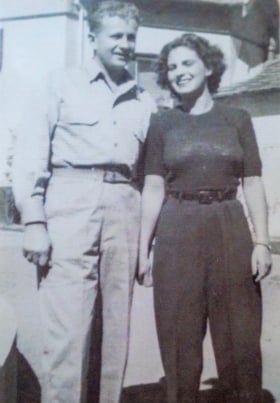

And then we went, Albert and I

went in the train

up to the Hydro [Majestic],

and we had two days honeymoon

because he had to get back to camp.

He was in the army.

The America army.

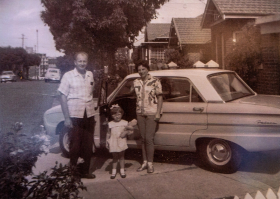

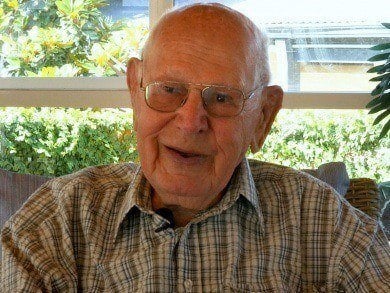

That's my husband with our first Holden.

When I married Albert he couldn't cook.

He couldn't boil water

when he went into the army.

And they wanted to put

him into the military police

and he decided, no he didn’t want to do it.

So he learnt cooking

and became the most wonderful cook.

Everybody came

and wanted to eat what he was cooking.

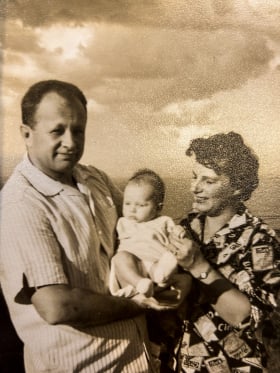

Albert and...

Ah dear Albert..

The bricks. I always had the bricks here.

I always had a brick wall in there,

whether I had bricks in my head

or something!

I had an art

teacher down in Millers Point.

I was painting for Julian Ashton.

And I remember when the wharf

burnt down in front of us.

At Millers Point.

And I painted it later on and I said,

“What a stupid thing to have painted that

after it burnt down and not before”.

In my mother's house I had a sort of a

studio upstairs and I used to paint there.

We lived in Bundarra Road.

I used to get up in the middle

of the night and start

painting, upstairs overlooking the harbor.

I think I called it

‘Be Back in the Morning’, didn’t I?

Left the toys there or something.

Movement and life, yes.

‘Kaleidoscopia’.

That's an interesting one here.

Some things are getting very hazy

and then they come for a milli second,

become clear,

and then I forget them again.

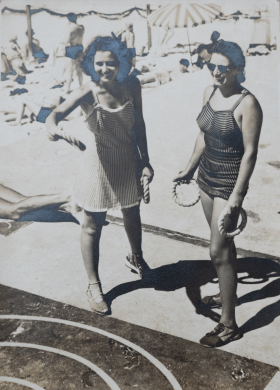

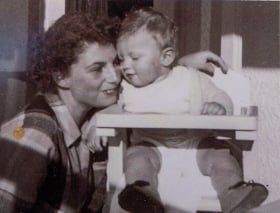

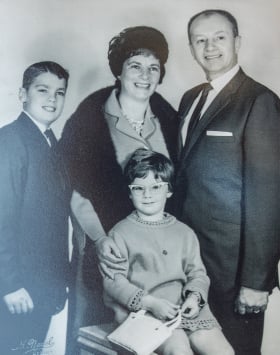

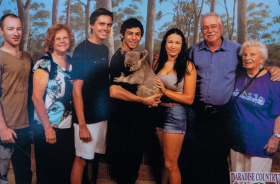

Ava and I.

And Albert.

And Charles.

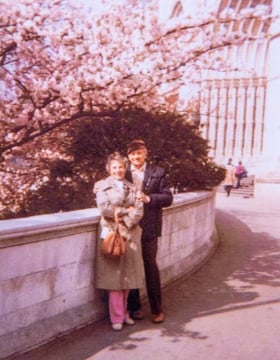

Ah, there’s Albert and I.

Yes.

That’s the two of us.