My name is Paula Bowman and I was born

on the 1st of June, 1922 in Yorkshire.

I had a beautiful family.

My father was in textiles.

Two girls and two boys in the family,

which was really nice.

So made me have a wee bit of a tomboy I’m

afraid.

And I was sent away to a French convent

at the age of seven

and didn't like that at all.

So I ran away a few times

just to cause a sensation.

I settled down after a few years.

So I ended up by leaving after

ten years as Head Girl.

So I was very proud of that.

I was captain of the hockey team.

And I loved netball too.

Every Saturday morning

we’d go on the beach

and if the tide came in, didn’t matter,

the horses loved being in there,

a little bit of water.

And then every year we'd would have

a gymkhana. We’d

have an egg and spoon race on horseback

and oh, I used to love, love riding.

I think I would have

been about eight or nine or something.

I was dying for a pair of shorts.

My father said, “Girls don’t wear shorts”.

So I got pretty sick about this,

and I said to my brother.

“Can I borrow your cricket shorts?”

They had little white cricket shorts.

And he said, “Yeah, yeah, yeah”.

So we were in this very smart hotel

in Belgium at the time

and I put on these little white shorts

and the shirt, and went down to breakfast.

My father saw me

coming in the dining room.

He nearly died. He couldn't believe it.

Couldn't

really make a fuss in the restaurant.

So after breakfast, he took me outside,

got mother to get her little box camera

to take a photograph of me with him.

He had his long, white flannels on

and I had these little white shorts.

And I've got the photograph today,

which meant a lot to me at the time.

But in the end, he just gave up,

I think, anything I wanted to do...

because I’d do it anyway.

I don't

think it was a very nice

little girl, was I?

Yeah?

Anyway,

leaving school,

I wanted to study architecture

but my father said “Girls don’t so that.

But if you really want to do it, if you go

to a finishing school first, in Denmark,

and when you’ve finished there

and you still want to do it, well,

we'll think about it.”

So overnight,

war was declared and I had a cable

from the Danish consulate

to say, “don't leave England,

war is inevitable”.

And just as well because they bombed

Esbjerg the following day

where I was to land.

Because I can't be just idle,

I went to the university

and did a Social Diploma course,

which was very interesting.

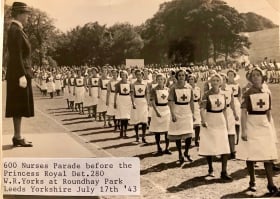

And at night time I used to work

for the Red Cross and I’d volunteer.

And I did weekends as well.

And it became a big thing in my life. And

nurses

were very, very short in those days.

And so they asked us,

would we take an abridged

nursing course

and go to York Military Hospital?

So my friend Margaret

and I decided, why not, we'll do this.

So we did.

So we gave away everything we were doing

and went to York Military Hospital.

That was quite a

difference in our lives, I could tell you.

And many, many homes in England

were turned into camp reception stations,

hospital relief.

And we ended up in Hull where

they were unloading hospital ships

and there were V-bombs

coming over in Hull

which was pretty terrible.

So that was quite terrifying.

But anyway,

we were young and we coped pretty well,

but it was a lot of experiences

for a girl who had just left school.

And I met a lot of

girls that I normally wouldn't have met.

One of the places that we were moved to

was Ranksborough Hall,

which was a beautiful old home

that had been given over

by the ‘Master of the Hunt’.

And the main homestead,

of course, was the hospital.

There’s a photograph of me

actually looking out of the window.

The stables underneath

were full of ambulances

and we were billeted where the grooms

would be.

Your sugar ration was in a little jar.

We had three little jars on the table

in front of you,

one for your sugar, one for something else

and one for something else

with your name on them.

And that was yours for a month.

That was to last a month.

But everybody was healthy.

We were all slim and

we had enough for our energy.

It was an amazing ration.

And I always said

that if they put that ration into a book

and sold it for diets...

that's what would be good.

One day they had a message from the local

aerodrome

saying

they were having a party in the mess

and would they send over five nurses

or whoever was off duty

to join the party for obvious reasons.

And so Margaret and I were off duty

and we were one of the five.

We went there with an escort,

a matron, very strict matron,

and we were formally introduced

to all the fellows,

which today would be unthinkable.

But that's that's the way it worked.

And of course, being

well brought up young ladies,

we danced with whoever

we were introduced to.

And then halfway

through, then we changed partners.

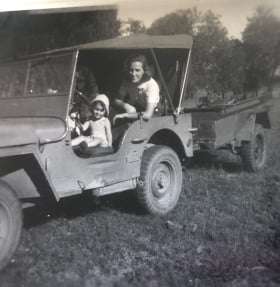

And that is how I met my future husband.

Because Margaret's partner was given to me

and that was it.

She never got him back again.

His name was Arthur Bowman.

So that was the beginning

of the romance really.

And it was a long way from town

where we used to go to the...

there was a pub there.

And one day he said, “Do

you think you could come

next time without uniform?” They’d

seen nothing but uniform for so long

and just wanted women to look like women.

I said, “Margaret,

have you got anything apart from uniform?”

because we had to go out in our uniform.

I said, “I’ve got a jumper

and I’ve got a tweed skirt or something”.

Nothing very exciting

because we didn't have in those days.

And so we did.

And my hair was down here.

Pageboy, you know.

So I just put a bit of ribbon,

bit of navy blue ribbon around my head.

And we had to cycle into town.

Oh Tina, you have no idea!

In pitch dark.

And had these little

lights on

the front of the bicycles with shutters on

because it had to do that.

That's all you were allowed.

Night in the dark.

In the country.

All the way from Ranksborough Hall

all the way down.

We left our bikes outside the hall there,

and then we had to cycle home at midnight.

It was uphill all the way!

I'll never forget that.

And then we were posted

elsewhere, over to Ely

And so that was the end of that

for a while,

until I had a message from Arthur,

my future

husband, to say that he was getting

leave and could I get leave?

And I wrote back and said, “No I couldn't

get leave at all during that period”.

So he said, “Oh well, I’m

coming over anyway”.

And I was stationed

at this time

in the Bishop's Palace in Ely,

which was absolutely beautiful,

and there was a big garden seat there,

and he used to sit on that seat

and wait for me to come of duty.

I said, “You've got leave”.

“Yes”.

“Well where is your crew?” “Oh

they’ve all gone up to London”.

I said, “Well

why aren’t you going up to London?” “Well

I didn't want to go,

I wanted to come and see you”.

So that was really the beginning of things

I think.

So anyway, he was a pilot

and he’d been into Bomber Command

and he'd been over to Europe

and he was partly traumatized

at times himself.

But nobody called it that in those days.

They just said they were tired

and you know, needed a break.

He was in what they call

Wellington Bombers.

I saw the Wellingtons setting off

one night to go over to Germany

and they were fabric

and they were literally shaking.

Awful to think that men

were saving their lives in these machines.

Anyway, he was soon transferred to

the Lancasters, which were much superior.

They really saved the War.

Wonderful machine.

Mother was working for the Red Cross.

Only rolling bandages and things but

she was doing something for the Red Cross.

Everybody was doing something.

And then if or as say,

we had a house maid

and another one you know

but they had to go,

they went on munitions.

So that's how we ended up with just Betty.

And my brother

Desmond, aged 22,

a fighter pilot, was killed in Burma.

And that was devastating for my parents.

Absolutely devastating.

The government wanted me

to take compassionate leave,

to try and do something with my parents

because my father was a workaholic,

was just sitting

traumatized,

and my mother the same.

They weren't drinkers

so they weren’t even drinking.

They just had cups of tea,

sitting, looking at one another.

It was all...

Didn’t move from the house.

So anyway, after a little while, I did

eventually get my father back to work.

It was Christmas time

and I suggested to my parents

that I had this lonely Australian

who had nowhere to go for Christmas

and how about, you know,

I said, “How about, would it be

in order to have him for Christmas?”

“Oh, yes” said my father, “provided

you don’t get fond of the fellow”.

Nearly said, “It's too late for that”,

but I didn’t.

Anyway, eventually I did get him over

to Beech Lodge, my home.

We went in to Leeds

just to do a bit of looking at the shops

and have a cup of coffee

and things like that.

And over the cup of coffee,

suddenly Arthur said to me, “When

are you going to

marry me?” And I said, “Oh,

why?” And he said, “Well,

when are you going to marry me?”

And that was the proposal.

That's all he said, as if to say, “I know

you want to, you know”.

That's all he said.

So anyway, we decided there

and then we wanted to become engaged.

So when we got to Beech Lodge, my home,

he asked to speak to my father.

So he was locked in the dining room

with my father

and put through the gamut

I might tell you.

And he was there for ages

and I was sitting on the stairs outside

thinking, “Goodness

me, this is going on for hours”.

So the poor man really went through it...

and my father's questions,

but in the end he won him over

and we were allowed to become engaged.

So that was the beginning of everything.

My father made the stipulation:

we were allowed to become engaged provided

we didn't get married

till after he’d flown

his complete tours over Germany,

which was understandable

having lost my brother.

And also my father

wasn't too keen on me going to Australia.

So he said to my future husband,

he said, “Would

you like to stay in England?” And he said,

“Well, yes, I could do that

and continue with my accountancy

after the War”.

My father said, “Well,

if you’ll do that I can article you

to an accountant in Leeds

and you know your future will be assured”.

So anyway, I was asked about this

and I said, “I don't marry

an Australian to

expect him to stay in my country,

if I'm marrying an Australian

and he wants to go home,

where his inheritance

is, that's where we should go”.

After we had

gotten the okay to get engaged,

my father, of course, to leave

no stone unturned,

decided to put a solicitor

on to the Bowman family,

which I was marrying into,

to find out something about them,

and unbeknownst to him,

my future

mother in law was doing the same thing.

And to my amazement,

I never knew until many years later,

that they were both using

the same solicitor.

Freddy was my matron of honour.

Didn't have any bridesmaids,

just my matron of honour

which was my sister

because she was already married.

I had nothing to wear, I mean I didn’t

go to a couturier

and have a wedding dress made.

We just bought something off the peg.

Literally.

And you had to have coupons.

So the family gave me

some of their coupons

so eventually we had enough coupons

to buy the dress.

I wasn’t very fussed

what I wore to be honest.

But there’s quite a nice shot,

quite a photograph isn’t it?

All the ones in the Australian uniform,

there’s two

I think, two in English uniform,

the lighter color.

And then on the other side

was Malcolm and Freddy

and the rest of the crew.

Many moons later of course

I became pregnant

with my first son, Arthur.

And so I got maternity leave.

That was really nice to be home

with my parents,

but they thought I was very silly

to have done that.

But anyway, they knew they would never

stop me doing whatever I wanted to do.

They never could. So, for us

to get to Australia, I had to go on

what they called the ‘Bride Ship’

and I couldn't tell you the performances

that went on that ship.

It was delayed for two weeks

because there was so many children

that they decided

they ought to have a child

specialist on the ship.

But actually,

I think we were waiting for the doctor

to qualify because his knowledge was nil.

My father drove me up to Southampton

to get out on the Stirling Castle

and when we got down

he said, “My dear child,

you must love him a lot

to do what you're doing.

Getting on that ship,

you don't know where you’re going to

with a little boy.” He said, “It

just must be the right person”.

So that was... He was obviously...

He’d lost his son

and now he’d lost a daughter.

So I could understand his sadness, really.

I said to my father,

“Please don't ask for any

special things on the ship for me.

I've got to go

the same as all the other girls”.

Little did

I realize, who the other girls were, but

he must have done something

because I had a cabin

with a hook-on bassinet for the baby

and only one girl

who didn't have a child in this cabin.

And I had my bathroom as well.

Now most of the girls,

there were five to a cabin,

with children.

I don’t know how they managed

but so many of them were so dreadful.

These girls used to lock their children

in the cabins.

There were a lot of toddlers.

Lock them in the cabins

and sleep with the officers.

And as for hygiene,

there was nil on the ship.

They didn't even bother

to wash the napkins.

No disposable in those days.

Anyway, it

ended up by getting

this terrible gastroenteritis

and I befriended

one girl,

who had married a teacher in Melbourne,

and she had a little girl called Betty,

same age as Arthur.

About nine months I think she was.

And she died on the way at Fremantle.

Must have been devastating

to that girl to land

and tell her husband

that the baby had died on the way.

You know, must have been horrifying.

Well Arthur got very sick

but he looked very healthy.

When I left, he was a big bouncing boy

and therefore he had a lot of resistance.

He was never a weakling.

And so when we came off the ship

in Sydney,

we had to line up to have a health test

and the doctor looked at Arthur and said,

“Well, you're a healthy young man”.

And I just said, “Yes”.

I made out he was very healthy

because I just couldn’t

get ashore quick enough

because I knew the doctor was no good.

So anyway, Arthur alerted his...

when I arrived, he alerted his uncle,

who was Dr Dougal Bowman,

who immediately got a bed at Children‘s

Hospital, Camperdown,

and Arthur was taken there.

And when he arrived he was very ill

and they said to Arthur and I, “Don't

leave the hospital, sleep

in the chair tonight.

We don't like your chances”.

So it was pretty devastating.

Anyway,

in the morning

this little cheeky boy was sitting up

in the cot giving the nurses

and clapping and going on.

It was dehydration

and the poor child

was given an intravenous...

and he was cheeky

and sitting up in the morning...

And was absolutely fine.

It was pure dehydration,

from the gastroenteritis.

Anyway, we were very lucky

that we got him to hospital in time.

Kanimbla Hall was a tiny apartment,

but it was ours

and it was just lovely to have it.

But I had no laundry.

It was just a bathroom,

a bedroom and

the living room and the balcony.

The balcony had a piece

of awning that came down

and that is...

we put the awning down and we put a cot

for Arthur on the balcony,

and he literally slept on the balcony

all the time.

That was his room.

There was a little kitchenette.

There was a little fridge,

a little stove and everything was tidy.

And I wasn't a cook anyway.

I had never cooked in my life.

A passionfruit.

I did know what they were and I said,

“What are those?”

He said, “Oh, absolutely delicious.

Put them into the fruit salad.”

So I said, “Oh alright.”

He said, “What

are you doing in the kitchen for so long?”

I said, “This stupid fruit

you bought, by the time

I’ve taken the pips out, there’s

nothing left.”

We'd been in Sydney

for quite a while and it was time

we felt that I met my mother in law.

So we didn't have a car,

so we went by train to Singleton

in the hottest day ever.

I think it was 103 in the shade

or something

with this little boy in the train.

And we got to Singleton

to be greeted with my mother in law,

who was very voluptuous

and rather frightened the little boy.

But anyway, it was my first encounter

with my mother in law.

And that she had this Jaguar car,

put us into the Jag,

sat in the back of the car

with a little boy who was dehydrated

at the stage, on a dirt road,

all the way to the property.

I thought we were never getting there

because I wasn't used

to the Australian countryside.

The homestead and three

share farmers houses.

They were all into dairy.

Beautiful property over the Hunter River

running down the the bottom of it.

The property was left to my husband

at the age of six.

His father died when he was six

and he was the only

boy it was to go to him. But

as they did in wills in those days,

it was left to my mother

in law for her lifetime

and that that was the way

they made wills in those days.

And so long as she didn't marry,

it was her property.

But if she married, which she never did,

it was to go straight to the son.

Anyway, one day

Arthur came home from work,

it was in Le Maistre Walker

in Sydney and he said,

“Would

you mind going to live in the country?”

And I said, “Well,

I've come across the world.

What’s the difference?” Living in

the country was quite a new thing for me.

I wasn’t experienced at all

but you learn pretty quickly.

The country friends that we made

have been with me for the rest of my life.

I mean most of them have passed away

now, but we've had some

amazing times with them.

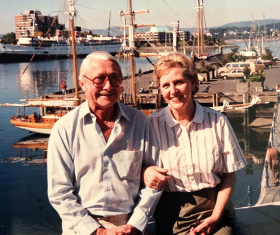

I cannot believe

that I am still here

30 years after my husband passed away.

We were the same age.

We were both 70 when he died,

which is pretty dreadful.

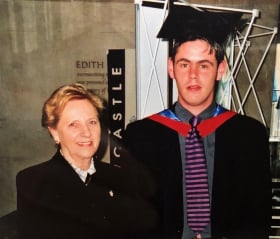

And then later, my son

Arthur, he passes away.

Same age, 70.

It's been the tragedy of my life

really.

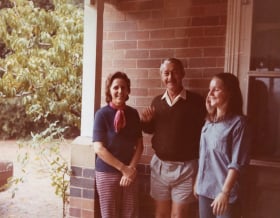

It’s a bit difficult, but I still have...

I'm still fortunate enough

to have my son, Antony, and

my daughter, Tina,

ten grandchildren, 16 great grandchildren,

which means I’ve got 26 grandchildren,

which is not too bad,

although I have lived 100 years so

that's my reward I expect.

Ever since childhood,

I’ve been interested in art.

We had a really nice studio

when I was at school and my happiest time

was when it was an art day

and we could go in there and paint.

And I did...

my first painting was a ship

on the shore at Filey Beach.

And I’ve still got the painting today.

1937 or 36

or something, which makes me about 12.

When COVID started

and there was isolation,

I had a lot of friends

who were in retirement homes

or nursing homes and weren’t

as fortunate as me.

And you couldn't visit them

because of COVID.

So I started doing little cards,

painting images on cards

and drawing flowers and birds and things,

and sending them

these cards.

Favourite owls.

A lot of my friends would say, “What

do you do all day, it’s so boring

when there’s nothing on television?”

I said, “Television?

I don't get near the television

set til the 7 o’clock news”.

And they say, “Well,

what do you do all day?”

I said, “I draw and I paint and carry on”.

And I said, “I find it very interesting”.