Closed captioned icon

View audio transcription

What are you proudest of in your life? Oh... you’re not supposed to be proud.

Josephine Mary Cannell. I was born in New Norfolk in Tasmania

on the 24th of February, 1918.

I've got certificates from the Pope for 50, 60, 70 and 80 Jubilees. If I can go, I think it's two more years, I'll be 90 years.

professed. Final vows. I’d like to get another one from the Pope before I die.

Collingwood. I still barrack for them.

I was watching every kick

and it went on to after 5:00.

And I couldn't believe because it looked as though they were going to win. But they may not have won if they'd... something else had happened. So I still sat there and people, I don’t know how many carers came and knocked on the door and said... I said ‘”I'm not coming”. “It's time for tea.” “I'm not coming!”

And in the end, a very nice carer, a lady, came down with a plate of sandwiches and a cup of tea to me.

grow Good ol’ Collingwood forever.

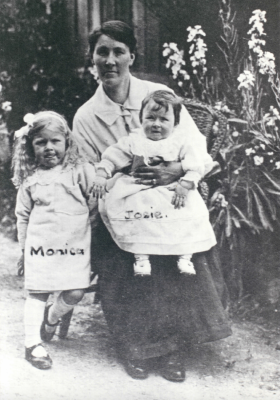

My mother

was

born in New Norfolk like all the others and

her

Grandfather Triffett

was

first warder at the mental hospital, which was the only one in Australia at the moment, I think.

And he gradually advanced until he was the Chief Superintendent there and that's when I began to know my grandad. Beautiful man.

One of the people who wrote things at that time

had written down,

“Now that they

Ben Triffett

is in charge of the mental hospital, the patients will be treated as human beings”,

so that was a lovely thing to write about grandfather.

My mother

became a nurse in the mental hospital

and that’s how my mother and father

through

both working at the mental hospital at New Norfolk.

My childhood was very happy because my big sister looked after me.

We lived across the road from the mental hospital

and we could run over there, go through the gate

and

down to grandmother's house any minute of the day

if we wanted to.

We knew that some of the

men

had to be kept locked up

and we knew that there were the others

who were allowed out into the gardens

and they worked there

for a few hours in the day.

The nurses

occasionally brought home

a patient for afternoon tea

and

some patients fell in love with some of the nurses and would do anything for one, but not for the other. And we just lived in the midst of it all.

I remember as well as anything

Uncle Joe had a

very long drive

beside his house

and all the people were inside talking about Grandfather dying and I thought, “I think you walk up and down when you’re sad”, so I went out into the drive, and I believe they were looking through the window at me as a four year old, I was marching up and down the drive trying to look sad because my second granddad had died.

Well, I suppose during the Depression years, we always thought we were so lucky

what was happening,

mother

always had

a beautifully, tasty cooked meal ready for us to eat every day.

Everyone in the street knew everyone else,

and opposite us there was a man named Mr Prentice.

He was back from the War and he had no legs below the knees. He had knees and he had pads that he could put on them. And he used to sometimes walk up and down just on his knees

and some people had other injuries, that, you know, were probably not so easily known about, but it was a sad time and a very hard time

there was no money round about anywhere

and all the businesses were,

you know, failing because no one had money to buy from them.

My mother got

the daily paper from Hobart

and

if she saw something that she thought my father would be good at,

she would send me up to the grocer’s. We did have the ‘phone on

but my mother had to have that taken away

because people were

coming to ring up and not paying for the call, and mum had no money to pay for the phone. So she had the phone taken away and if she saw something in the paper she would write the phone number down and send me up to the grocer and ask the boy up there to ring and see if he could get an appointment for my father.

And he did. They answered straight away and said, yes he sounded what they wanted so he did get that job in Hobart and at the end of 1925 we all packed up and moved down to Hobart.

There was a state school. My sister and I attended that. She was there for three years and I was there for two.

Now that photo of the children in the state school , in that top row of boys, most of those were grown men when the Second World War came. They nearly all went and they were nearly all killed in it.

I know there were a pair of lads in that photo who were brothers. They were

both... I know they were both killed.

There was a... and there was, the Quayles were the two boys who were brothers. And there was somebody... forgotten his name and I used to be able to reel them off but because I had I haven't been able to see them...

I was a young teenager. That was, I think, worrying my mother.

And my mother made me go back to school,

St Joseph's College in Hobart.

only to find

that I was the only one in the class

and I wasn't happy and neither were the nuns because I was a nuisance, I think.

Mum came home, just came into the house,

she didn't say anything. So after about five minutes, I said, “Mum, what did Sister Eileen want you for?”

And there was dead silence and then she said, “The sisters think you have a vocation to be a nun.” And I didn’t say anything. And she said, “What do you think?” And I said, “Perhaps it is that mum. Yes. ”

On the last weekend that I was at home before I entered the convent

my sister and I had got ourselves all dressed up ready for a dance.

And when we went to say good bye to the family, my father remembered that he had booked with the photographer to take a family shot.

So my mother had to get my two little

brothers, clean them up, put them into their school suits,

and we went into the photographer and he took a family photo

of us.

The six of us were displayed and my young brother sitting in the front I think between my mother and father. He thought he looked the best...

anyway...

The Sisters of Charity,

the five that came out,

they were the first to set foot on

Australia soil.

Three of those original five

were tormented by a young

Benedictine who was left in charge.

He said he'd send them to New Zealand and he couldn't find a boat going to New Zealand.

But he found one going to Hobart.

So he told them to go down and get on that. They did

and they were welcomed into their new home.

1847,

St Joseph's Church.

If you feel

to

a religious,

you start

training by going to a novitiate.

And I remember saying to a priest I was talking to one day and I said, “I believe they are going to do this and that and the other thing to us.” I said, “I don’t know how I’m going to cope.” And he just said, “Oh you’ll cope alright. You’ll find you’ll cope.” And I did when it came, when the real thing did come.

I had had my 16th birthday in February and I went to the novitiate in June.

The mother house was St Vincent's Convent.

It’s on this magnificent property there at Potts Point, just down below Kings Cross.

We knew that it would be a different kind of life.

Rules to obey.

Bang, bang, bang on the door.

Getting up early in the morning.

Get up.

Ablutions.

Got dressed.

Go outside, line up,

two by two

and go to Mass.

Reading.

Morning tea and then we had

hot meal

at midday.

Afternoon would be

time of recreation,

tennis or basketball.

Physical exercise.

And afternoon tea.

Study in any spare time that we had.

Geography, English and art.

After the six months of postulance you became... you were clothed in the habit.

You did two years as a novice then,

with a white veil at home

black veil when you went out.

Mother General visited

the people who were ready to be

received as novices.

and she said something about the name.

And I said, “What about St Aloysius?”

The Italian for Aloysius was Luigi. She said, “There’s one that's a retired nun. She's up at the convent in Lismore.”

She said, “She's a funny lady, she's a German and she loves having a go at people.” She said, “I’ll write and ask her if you can have Luigi as well.”

And she sent for me one day and she said, “I got an answer from Luigi,

it's eight pages long and it's full of what she thinks you should do and be.”

So I got Luigi for two years

and then I kept that until

we were able to change back to our names.

And then

you make vows, final vows, the important ones and you received a brass crucifix

and a gold ring

and

a black veil to wear at all times with a white cap under it, and a black habit with a black cape around it

You kept wearing that until the

Vatican II

came along.

and we were given the choice of

looking like ordinary woman a bit more.

After I had done my two years,

I was allowed to teach.

I taught grades four and five,

boys and girls, seven and eight.

St Raphael’s

St Teresa's.

St

John's East Melbourne

Then I went to Collingwood.

1973

St Columba's Essendon

So I was always prepared,

tried to make it interesting.

They tell me I was a good teacher, not that any of them bothered to tell me.

Just can't get my head around what's happening at the moment. The band of age, people, seem to have forgotten everything that anyone tried teach them about minding their own business, being kind to other people and not making a nuisance of themselves.

with the police that has become so rampant. And I just don’t know what is happening now.

And I pray a lot too. I don't feel it's impossible but I just tell God sometimes how he could just take Putin to sleep one night and not get him up again. And the same with that stupid fellow in America. He's trying to be the... take over America again.

And there's so many people who are not thinking properly. Urging him on. If he could just have a nice silent death or something. I do pray for that. And I don't whether God’s saying, “What about yourself? Do you want to be put to bed, to sleep, and not to wake up?”

When my mother was dying, my sister let me know

and when my mother started to talk to me and

and so I was talking to her for a while and then I said, “Mum, do you realize that maybe, in an hour or

so, you will be standing in front of God?” And she looked at me. She said, “And your father.” “That's right., Mum. Yes. You’ll be there waiting for him.” He'd been dead for 13 years. So hope he was all bright and ready for her when she arrived.

Thanks To

Sr Cathy Meese, Elizabeth Nicol

Josephine Cannell

"we knew that it would be a different kind of life"

Centenarian nun, Sister Mary Luigi: A Nun for almost 90 years

Now, 105 year old, Josephine Cannell, also known as Sister Mary Luigi, has dedicated nearly 90 years to the Sisters of Charity. Born in 1918 in New Norfolk, Tasmania, Josephine’s path led her to Hobart and then on to Sydney where she joined the convent. She began her lifelong mission of teaching and ministry at just 16 years. Josephine has authored two books, ‘A Seed that Grew: The Story of St Columba’s’ and ‘To the Beckoning Shores: Urged on by the Love of Christ’, which delves into the historic journey of the Sisters into Tasmania in 1847.

Age in Video

105 yearsDate of Birth

24th February 1918Place of Birth

New Norfolk, Tasmania, AustraliaThanks To

Sr Cathy Meese, Elizabeth Nicol