Closed captioned icon

View audio transcription

Full name is Barbara Woodward.

I was born at Port Pirie

in South Australia,

up towards Port Augusta, in 1921.

My mother's name is Marjorie Moffat Wardell.

And my father was Oliver Holmes Woodward.

"My father actually met her

when she was about 14,"

"and he said he never could

explain his feelings for her."

"Father was a tunneler

in the First World War"

and being the Victorian gentleman,

he wrote to her father to say,

did he mind if he corresponded

with Marjorie,

just as writing to a soldier,

not telling her

that he cared about her.

That's my mother's

"engagement photograph,

wearing the miniature"

medals of her fiancé.

In 1934, father had written up

his experiences as a tunneler

"for the Australasian

Institute of Mining and Metallurgy"

"and then later on,

he thought he wanted to record"

his own

experiences for himself and the family.

He wrote my story of the Great War.

In those days they were almost...

"I don't know

whether they were officially told"

"but they were not expected

to talk about it."

Which was wrong.

Both from their point of view and from

from ours really.

And a man

"ran across a copy of this book

and read it and said, "

“What the devil were miners doing in the war?”

What were tunnelers?

And when he'd read the book,

he was determined to make

"some sort of a film

to honour them, really."

And this is

the film.

Woodward?

I understand you’re a demolition man?

Yes, sir.

"It was father that actually threw

the switch."

That blew

the trenches up.

But because he was underground,

he didn't see the result.

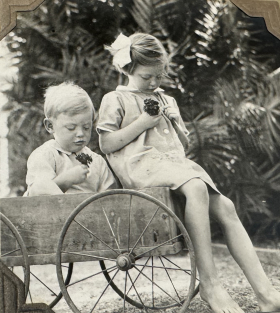

I have two brothers younger than myself.

"One, three

and the other six years younger."

"My father after his services

in the First World War, was working"

with the smeltery at Port Pirie,

which smelts the ore from Broken Hill.

My childhood memories

don't really begin

until I was about six,

when he was manager

of the smeltery.

Father was strict but very fair.

And because he knew that we would

always behave ourselves with him

and do as we were told, he used to take us

to the places that he worked at.

So I grew up

with memories of

roaring furnaces, smeltery and

casting lead and

Port Pirie was a strange sort of a place.

When you were a child

"you're interested in,

but you don't question"

the place that you lived in.

And it really was quite

an extraordinary harbour.

Piles of wheat

"that were waiting

to be shipped by the clipper ships."

"So that you had clipper

ships at one end of it and steamers"

at the other end loading lead.

I went to school

at Port Pirie West

because father believed that

you should go to the government school.

"And I began French

because there was a woman."

who had come to Port Pirie who was German

"and why she was teaching French

and not German, I don't know,"

she taught us the international symbols

for pronunciation for learning a language

after dancing class on Saturday mornings.

My father made an overseas trip

on behalf of the company in 1934

and he was away for eight months

by ship and train and...

Whereas now you’d fly over and back in

you know, ten days sort of thing.

"He was offered this job

to manage the north mine in Broken Hill."

"And he and my mother,

I never questioned them on this,"

but I should have,

had to decide wit h him in London

and she here,

whether he took this job.

This new job.

When you had to

book a telephone conversation

"and sit

and wait for your call to come through,"

or send cables, and

what a decision they had to make.

Anyway, father became

"the manager of North Broken Hill,

and I lived in Broken Hill"

"about four years

as a secondary high school student."

"Broken Hill

High School at the time was a sort of"

high school TAFE mixture.

I was in the academic stream, but it also

had a stream which enabled

girls to manage a house,

or boys to do metalwork or woodwork.

And then back to Adelaide.

Woodlands Girls at Glenelg.

When I was going to university,

everybody had to do something

for the War.

All the boys dug up the university lawns

to make trenches that we would leap into

if the bombing came to us.

"But we were sent

to the children's hospital"

because the nurses who were overworked

and underpaid, got a break

while we looked after their,

mostly polio patients.

And also I side track, had a

certificate of proficiency

in netting for camouflage

of trucks and things like that.

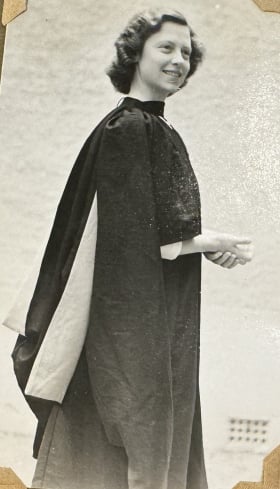

The Adelaide University

was one of the acceptable universities

for the Sorbonne.

And I had majored in French

anyway so I was going to spend

a year in France at the Sorbonne.

"I did morphology,

which was a form of words."

"The hostel that we were living

in, which was on the Boulevard San Michel,"

"just opposite the Luxembourg Gardens,

was entirely female,"

and a very famous American lady,

Miss Watson, and Miss Watson

"she was able to help

a number of people escape."

during the war at this student hostel.

Because the hostel was founded by America,

"we got into a lot of places that we

otherwise"

might not have been able to see.

"museums and special churches

and every weekend"

there was some sort of organization

for the American girls, and the two

mug Australian girls who were living there

were able to join in.

"We did see a number of things

that we wouldn't have"

"otherwise had the opportunity ever to see

probably."

"Went overseas in 1950 and came back

to Australia almost four years later."

Mother and father were in Hobart.

So I finished up holidaying there

until I got a job

through father's interests,

because he was still a director

of North Broken Hill, and said,

you know, if you ever hear of a job

that might suit Barbara, because

in Hobart in those days,

you were probably just behind a counter

or in typing pool or something like that.

So I get the job

running the office for Sir Henry Somerset.

Associated Pulp and Paper Mills Limited

which made paper in Burnie.

His mother is my second godmother.

So, you know, it's all been like this.

Perhaps that I didn’t marry.

No, I just sort of pottered along.

I wasn’t particularly

happy or particularly unhappy.

Maybe that’s how I’ve lived as long as I have.

Barbara Woodward

"I grew up with memories of roaring furnaces"

From Port Pirie to Paris!

Born in Port Pirie in South Australia, Barbara’s upbringing amidst the smelter and industrial harbour shaped her early years. She moved with her parents to the remote mining town of Broken Hill. Barbara’s father was a tunneller in World War I. His memoirs inspired the film, ‘Beneath Hill 60’. Following her years studying French at Adelaide University, Barbara travelled to Paris in 1950 to attend the Sorbonne.