Closed captioned icon

View audio transcription

Some people used to think that I was mad.

“We can't understand you two, one minute

she's going to kill you

but if I say something [bad] about you,

she’ll want to kill me!”

And they could never understand

how we got on.

Howard Shelley.

Howard Alfred Shelley.

I was born in West Bromwich.

Part of Birmingham.

My parents,

Alfred Shelley

and Margaret Shelley.

Well, I'm an only child.

My mum worked at

the Hercules cycle factory in Birmingham

and my father worked

at the General Electric Company.

My Dad always used to get me to put his bets on

for him with the local bookie

when I was a kid.

And, I consequently bet on horses

all my life.

Much to my

despair at times.

Not very successfully, I tell you.

My grandmother,

my father's mother,

she lived in West Bromwich.

She was was a miner's wife.

My memories of her is

just sitting by the stove

with the kettle on.

She was a very severe woman in black.

And they heard

she'd been playing around with some bloke.

I remember we walked down there this day,

we found we were in the midst

of a bit of a family business.

She sat there and looked at us all,

and she was a tough old bird.

Although she was playing around

with a bloke she's a tough old bird.

And, she said “Alfred!

Make this tea”.

She didn't get off her bum herself mind you,

and Alfred

had to get up and make the tea

and look after us whilst she sat down and

had court, you know,

“The rest of you can listen to me.”

On our holidays,

which in those days

consisted of one week.

That’s all people got off.

Dad would rush home on the Friday night,

we’d grab a suitcase,

jump on the train,

and go down to Torquay.

And my greatest pleasure was

the company of donkeys on the beach.

I was 14 when I left school.

You had to leave school at 14

unless you were

clever enough to go to secondary college

which I wasn't.

I went to work for a plumber.

and I got ten shillings

and sixpence a week

which I had to hand over to

my Mum every Friday

because things were tight.

All my friends were working in the

munition factories

and earning good money.

I thought, blow this, this is no good,

they're going to dances and pubs

and so

my mother got me a job at

the cycle factory.

The war started.

I was conscripted into the army.

And I was posted

up to Catherine Camp in Yorkshire.

I walked into the canteen

in Catherine Camp

and this young lady was behind

the counter.

Mary Bernadette Woodgate.

She was in the

Women’s Army Corp.

So a bit of banter started.

Bit of cheek

and I finished up marrying her.

My wife was Irish.

County Kilkenny.

And she loved a good argument

or a good fight.

She’d fight anybody.

You upset her and boy were you in trouble.

You could have been

six foot four and she was five foot two.

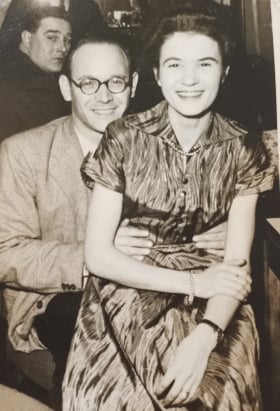

Yeah, she wasn’t a bad looker, was she?

Different to me!

I remember the duty officer

and the duty sergeant come marching down.

“Where’s Trooper Shelley?”

“We understand you have

a girlfriend in the ATS.

Private Woodgate.”

I said, “Yes. What’s she doing now?”

And he said, “Well

you better come with me.”

And we went into the cookhouse

and there is Patsy with a knife.

Patsy had took offense

at something this girl said.

And it got a bit more than fisticuffs.

Patsy was going to kill her.

What for I don't know.

I could talk sweet-talk her

and so I had a chat with her.

At any rate Patsy dropped the knife.

We did calm her down

and they took her away

and she got seven days’ ‘jankers’.

She had to go down the cookhouse

and sit there all day

with a big bag,

bags and bags of potatoes, carrots and like

and peeling them all day long.

But she was lucky she got away with that.

If it had been like a civilian court,

she’d have been in big trouble.

I remember when we first finished our

training,

all gathered together, bunged on a train,

given the kit bag, I was kitted out and

we were going overseas

because the war was

in full swing.

All sorts of rumors

where we were going.

We thought we were going out to Burma,

out that way,

because of the clothing we were issued.

Light khaki. Not heavy.

We were traveling through the night.

The train pulled into a station.

The Red Caps got on, the hated Red Caps.

That's the military police.

And they just said, “You there!

Line up on the station.”

We were marched off

down the road a little way.

Out the train went

with the rest of the boys on it.

And

most of those boys were,

unfortunately,

you know killed.

Pure,

absolute pure luck.

I was in the army for

five & a half years

and never fired a shot in anger.

I never went abroad.

I was always stationed [here]

and they moved me around.

I was one of the fortunate ones.

I went to a place in

Chertsey in Surrey.

‘Fighting Vehicle Proving Establishment’.

It’s where the armourment factories

were rapidly

making tanks and armored cars

and they used to rush prototypes

down there and we had to test them.

We’d jump in a tank or or a car,

trying to bash the car up.

Not smash it up, like dent wise,

but drive it as hard as you could

and make it break down.

They find out why it broke down

and make sure it doesn’t

break down again.

We had friends and

myself and the husband went for a beer.

The two women were having cups

of tea at home and God knows what.

When we got back to the house.

after being in the pub,

the place was strewn with papers.

it was all about going to Australia.

The couple were going to emigrate

and so by the time I got home that night

I think we were going to emigrate.

And we got on the Fairsky and

come out to Australia.

My father was on his own then.

He came to see us off on the ship

and Southampton was

the last time I saw my father.

We arrived in Fremantle

and so we got off the ship.

There was a line of desks

and that on the wharf.

I walked up to the bloke

and put my hand out to shake hands

with him.

He just ignored it.

And I said I was

a truck driver which by that time I was.

He said,

“Trucks drivers are ten a penny here.

We need people in the building trade”.

And I said, “Well that's nice isn’t it,

to tell me now!

I'm here with two girls.

A wife and two girls”.

He said,

“Well if you don't want to get out here,

if you go back on the ship,

see the purser,

and the ship will go to Adelaide

or Melbourne

or Brisbane.

And after that you're on your own

to go back to England again.

I thought this is a great introduction,

considering

you're asking for migrants to come

but that's the sort of greeting we got.

And that's what we did,

we got on, and when we got to Melbourne

they called us up.

There was a different reception

all together.

Had an interview and

we were put in

the huts used to be

behind the Exhibition Building.

And he called me in the office

and he said,

“Would you take a job in a factory?”

And I said, “I’ll take any job.

That's what I came for.”

And up there in Albert Street there was

a factory.

A. G. Healing.

They made televisions and radios

and things like that.

They said, “Yeah, here, we’ll give you a job.”

And then they also said,

“If your wife’s looking for a job,

we can give her a job.”

And I started my working life there

and worked there for 20 years.

Thanks To

Lisa Biviano

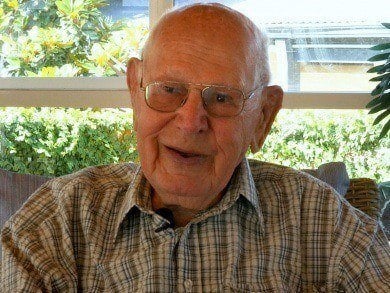

Howard Shelley

"I was one of the fortunate ones"

A Journey from West Bromwich to Melbourne

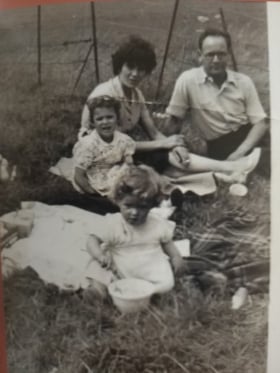

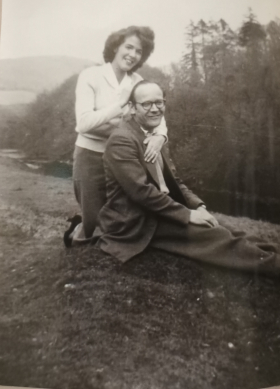

Born in the coal mining region of West Bromwich, England, Howard’s early years were shaped by hard work and resilience. During World War II, he served an essential role as a test driver for prototype tanks and vehicles, contributing to the war effort in a unique way. After the war, Howard and his family took a leap of faith and migrated to Melbourne, Australia, where they built a new life filled with hope and opportunity

Age in Video

100 yearsDate of Birth

21st July 1924Place of Birth

Birmingham, United KingdomThanks To

Lisa Biviano