When I was five I was out in the garden and this aeroplane flew over and I rushed in and brought my mother out to see it because it must have been the first one I’d seen. You know, I was so surprised. And my grandma was there and she patted me on the head. And she said, “And I wonder what other wonderful things you'll see in your lifetime, my dear.”

My name is Jose Emilia Petrick. I was born on 14 February, 1924, since Valentine’s Day, much to my parents

joy.

I was born in Boscombe Hospital,

a suburb of Bournemouth, a big seaside town on the south coast of England.

Well, I went to the,

primary school in

town called Christchurch, which was 5 miles from Bournemouth.

Our house faced the meadows. It

was called Fairfield.

We looked out over the meadows.

Butter cups and daisies and a couple of white swans.

Grandma lived with us.

seemed terribly old. She was 70, had white hair, sat by the fire all day.

Farmer brought about 20 cows in every morning at 8:00 and they just grazed all day and he’d come back at 4 and collect them, take them back and milk them.

We had

Oh. Fresh milk. I don't think it was pasteurised or anything like that.

And then this goes down in to the sand

we had our beach hut.

I remember going to say to

mother, “Daddy, if you’ll only buy us a beach hut,

I’ll never ask for anything for the whole of my life”.

When I was 14, we went down to Cornwall for a holiday.

Had a lovely fortnight, going to all the villages and the beaches.

The second

year there was all this talk about Hitler, Hitler. Oh, it's just rubbish, you know, it's just newspaper talk. Germany would never, never dream of

invading England. And you know, we sang ‘Rule, Britannia”. You know, England was the most wonderful place.

And when we got home, our aunt and uncle had been housesitting for us. And Auntie Nest saw us coming, ran out and said,

“Oh, I'm so glad you’re home safely, we think there is going to be a war. Mr Chamberlain is going to speak to everyone 11:00

Sunday morning and we think he's going to declare war on Germany.”

I am speaking to you from the Cabinet Room at 10 Downing Street.

This country is at war with Germany.

Well, England went straight into war mode.

The first thing was all the houses had to be blacked out... Afraid the German planes would come. My mother made new curtains for all the house.

The men who were too old to go in the army or were rejected on health grounds, were called the Home Guard.

They walked around every road to see there were no splits in the curtains; but they weren’t drawn properly.

One night there was this banging on the door, “Hey there! You want the Germans to come upon us all, do you? Why look at your curtains!”, There was one little split.

We never had a split afterwards.

was

was going to Bournemouth School.

And suddenly I think it was

June,

they rang the school and said all the French troops

we’re coming from Dunkirk and they were taking over all the schools at Bournemouth

as accommodation for all of them so we wouldn't go to school for a fortnight.

They had nothing to do all day and they were all shell shocked. All our class went down,

just where the beach near the pier.

We were 16 and

we all talked to the French soldiers every day. And then, after the fortnight, we went back to school.

We had to go straight into doing our exams because that’s when it was. And the French examiner for Oral French,

when I'd finished. he said, “I cannot understand how all you girls are so fluent in speaking French.

I've never heard such fluency in my life. And we all had merits.

Then, when I was 18,

I started my nursing training at Boscombe Hospital and,

got sinusitis, which is now, just a nothing, you have antibiotics. But all the antibiotics went to the troops, civilians weren’t allowed any.

And then, at the end of the year,

when we took our prelim exam,

I couldn't do it because I had a temperature of 104.

So I went into the Land Army.

I then went back to Portsmouth.

I had to start again, the four year training.

The hospital had been bombed badly before I went there, and they had taken over a

big house in the hills

and I was on the women's wards.

You know, there was all this talk

about when D-Day will be.

All the soldiers buzzing around. “Hi! Hi beautiful! What you doing tonight, beautiful?” and off they’d

And then I went home for my days off and there were no soldiers.

Nobody around. The town was so quiet. My mother said, well we think D-Day is going to be any day.

Oh, she said, it’s going to be terrible.

In England, General Dwight D. Eisenhower and his deputy commanders chart the liberation of a lost continent, plan when and where the mighty armies of the United Nations will strike.

Today, northern France is that battleground.

So I went back

on the train and the next night

where I went on that ward in the morning,

it was silent.

yeah.

All the beds were made

was nobody. No sister, no other nurse. I was the only one there.

There was this huge table with cupboards underneath. This was piled high with cotton

did that until 10 o’clock and then, 10 o’clock I went into the dining room for a cup of tea.

Another of the great decisive battles of world history has been joined. This is the day for which free people long have waited. This is D-Day.

When I went back,

at 10:30 that morning

there were these four,

They were all lying against the white pillows.

They were all bandaged, cotton bandages. Splits for their eyes, splits for the nose, spits for the mouth. And their arms and fingers, all separate

bandages. And I turned around, and through the windows I could see this cavalcade of ambulances

slowly crawling up, bumper to bumper and khaki signs with the red cross. And they came around and stopped and all these orderlies appeared and they were pulling these patients.

Suddenly all these strange doctors arrived. Nurses, they were giving them drips

They had to give them saline. They couldn't give them blood. There wasn't time to check their blood.

So I was going past a lieutenant’s bed, his leg up in an extension. He said, “what you doing tonight nurse?” I said, “First of all I’ve got to ring my mother in Bournemouth and see how she's going.”

He said,

“You know the Bourne Hotel?”

I said, “of course I do”. He said would I ring his mother?

“Dad went down in a submarine.

They all drowned and I’m all she's got.” So, all the way home, I was thinking, “what shall I say? What shall I say?” No, I won’t introduce myself. As soon as she answers, I’ll just say “Good news.

Good news, good news”. So the phone rang and there was a little voice, “Hello?” I said, “Good news. Good news!”

“Oh. Thank you”, she said.

So I said, “your son’s alright. He's got a broken leg. He’s in hospital, not far away. But he’s very well and happy and he asked me to ring you and tell you he’s alright. Oh, all she could say was ”thank you”.

Hostilities will end officially at one minute after midnight tonight.

Tuesday, the 8th of May.

I was working at the outpatients,

and the surgeon was busy. He was a very tall, slim man. He never spoke. And he was very busy cutting this dead skin off.

But in the interest of saving lives. The cease fire began yesterday to be sounded along all the front.

The door burst open and in comes an assistant,

“Hooray, hooray. The war’s over! The war’s over.”

The surgeon have this dead skin. “Hooray, hooray. Peter will be home.” Peter was this fighter pilot.

That night, I think we all went to town and just dance to the town bands.

Oh, and the church bells rang. The church bells we’re allowed to ring.

It was just so exciting.

No more bombing, no.

We.

When I was a kid,

I won this book at school called “The Countries of British Commonwealth”. And

the first country was Australia. Of course in those days

they only had black and white pictures. There was this tall slim man dressed in dark clothes on this huge black horse. And he was surrounded by what looked to me,

like hundreds of

cows.

And the caption was: “One man and his wife might live a hundred miles to the nearest town and a hundred miles to the nearest neighbour.” And I thought, “Well, how could one man and his wife milk all these cows, twice a day and what did they do with the milk?”

My father said ask your school teacher so I asked the school teacher. “I don't know, dear. You’d better go and find out, hadn’t you?” . And so then when I was doing midwifery, the girl I was sharing

brought out all these pamphlets from

Australia.

Oh it looks so lovely,

the pieces we learnt about in

This is a ship out. Came out. Out

We got on the liner at Southampton.

The fellow who met us from the ship in Sydney

in

That,

was English and she said, “Oh, I’m so glad.

If you two girls come, I'll have an all English staff.”

Balmain in those days was just a shabby old filthy town. And there was rubbish in the road. And I said to… We may as well stayed in London

If we’re going to [work] with an all English staff. Why aren’t we here?

We come out here to see the world.

We got jobs

at the repat hospital.

When we were at Concord, everyone said

how nice Tasmania was.

So we went to Hobart

A hospital there.

Then,

I was working in Adelaide.

I was at the CSIRO

as a store clerk.

I wanted to see a cattle. station before I went home.

And there was this ad in the paper

for a companion helper in Oodnadatta. So I looked on the map.

I didn't really want to go there, but I thought, well, it’s a step. you know?

I thought over, but I think I’d be just too lonely,

so I forgot all

about it. And a month later, I had a letter from the sister of the other station out of

Alice Springs.

This sister had a little girl of

7 and a little boy of 5

I told this lady that I really only wanted a job for 2 or 3 months, you know, I was trying to go around the world. Ha ha.

So the plane took six hours in those days.

I had to go out to Parafield.

I had to be there by five.

Pouring with rain.

It rained every day in Adelaide, and I'd taken my winter coat, naturally, from England

fur gloves,

stockings, shoes. Velvet corduroy dress. However, when we get off the plane at Alice Springs at midday... There, the women in sun dresses and sandals

and the men or wore shorts and shirts. Couldn't believe it.

There was no one. No one from TAA at all.

There was nothing there. Nothing. No sign saying ‘Airport’

or ‘Alice Springs 7 miles’

There were only three women on the plane

So when we got off the plane there were three men waiting. One lady said, “we can't leave you here”.

So I said, “where are you going to take me?”

And she said, “well, where are you going?” And I said, “Well, to a cattle station 300 miles away”, “Oh, we couldn't go there. Come on darling.” So she and darling went off. And, a little voice said, “Someone will come, someone will come”.

.

There was only a rock to sit on and the flies were terrible. So I took my coat off and it was so hot because my dress had three-quarter sleeves. Right. And, anyway then this dust came down, and a

funny four wheel drive. An ex-American. He said,

“I’m the taxi driver miss.

Mac

couldn't come because Mac had gone to

the railway station to get your trunk. “

And we got to town and

Mac comes around with the truck and

Rose got in the back and

there was little boy, Kerry,

who I was teaching, and little boy Jock, aged three. Little boy Jock will be 80 tomorrow and he’s invited me to his birthday party. And I sat in the front with Heather.

We went out of town.

Bitumen for the first 40 miles and then

we turned off.

So we’re going along this road, without seeing a soul. Not a soul. Not a horse,

not a cow. It was supposed to be cattle country. Nothing.

There was this house, but

no sign of life there. What are they busy doing? There was nothing. You couldn't see a vehicle or anything.

Anyway, then we had a hundred miles or more to go. On just a dirt road.

And the turn-offs and nothing was marked. Just the middle of nowhere. And then we go through a fence, you know, a big wooden gate.

It went on and on and on and on.

I tried to make conversation because we went over all these dry creeks and river beds that were as dry as a bone. And I said, “Why don't you have bridges over all these?”

“Oh, don't know.” So,

so we came to a little house on the hill.

And this lady who had interviewed me [had said]

what a lovely garden Rose had and I was looking forward to [like what] my mother had, you know, a rose arbour over the front gate, rhododendrons and roses and everything. There was nothing! Nothing. No fence around the house.

In all the papers we had about

Australia, how modern and up to date [it was]

We went in the kitchen.

They had wood stove. I thought this is medieval England. A big log fire burning. A bucket of wood. I can’t believe it!

had told me by letter, I must bring a torch and spare batteries,

because when Matt turned the

generator off.

suddenly! Everything's black and silent.

the world's come.

so

you can’t, everything's pitch dark. I just couldn't believe it.

I turned my little torch on.

curtains. And they come down on me.

They clattered down and I

go to pick them up and realized the curtain rod

spear,

one end is all blood red. Oh, God.

There was a little room

outside.

The Aboriginal women had cut all these rushes and sewed them together side and they were walls. And Matt made a cement floor and this was the school room.

10:00 we stopped for the School of the Air. That was on a little radio. You know, a two-way radio.

School of the Air had just started but there was only one teacher.

Monday, wednesday, friday for about quarter hour, where the teacher would talk to all the grades, you know on nature or history or geography. Very different from now.

The first teacher was a chap called Mr Kissel

and Hartley Street School was the primary school in the town. And he just had the end of a passage with a chair there, a table and this little flying

doctor set above the wall. And he’d talk to all the children,

and when he’d finished a story they’d all call back and say, “Thank you very much Mr Kissel”.

I taught that little boy for grade one. First he had to draw a picture for a diary and so I said to his mother whatever shall we do? She said well just draw a hill like that. Then people, you just draw round circles, stick bodies, stick legs.

He spent hours doing

all these brown streaks, so straight and sent it off. But weeks later it came back. Teacher says, “Grass is green, dear”. Well, I wasn't going to tell him after all all the hours... he's never seen green grass, so I said, “Teacher says that's a beautiful picture”.

You listen to the 8:00. First of all the medicals. But of course

hundreds of people are there. They all hear the medical,

you know, what someone's troubles were.

"Everyone had a big Flying

Doctor medical case"

all the medicines and bottles,

were all numbered. And so if the doctor said, you know, take two teaspoons of

bottle number six or something [like that]. got

It was a week before I was due to leave, and I went out and had a cup of tea in the kitchen.

And the children’s father came in with this tall, dark handsome fella, and I was introduced to

Martyn Petrick, who was a neighbour.

As we shook hands, this voice said, “This is the man you are going to marry. This is the man you are going to marry”. So, anyway,

the next morning, we were doing school and the children's mother come in and said Martyn’s sister just called on the two-way

radio and said they'd come over and pick me up to go over to their place for the weekend. So, oh well!

The following Friday

I had to go to town. It was the end of school term.

I went to the

TAA [office].

I thought I’d go to Darwin.

See if I could get a job in the hospital.

As I was walking out of T A.A, who should in but Martyn Petrick. He said, “What are you doing here?” I said, “Well, I thought I might go to Darwin”. He said, “Well I thought you were here next year.” I said, “No, I was only three months.” “Well, why don't you tell me?” I said, “you didn’t ask me.”

So he said, “Well why don't you come back to Mount Swan with me and have Christmas and then go to Darwin afterwards”.

So on Christmas Day, he asked me to marry him. And it just seemed like everything was in order, you know, so

I agreed.

Only came for four months.

You know, I just wanted to see a cattle station and I wanted to go around and see more of Australia and the world.

And I married the boy next door.

There was only one church in Alice and that was the Church of England.

Very high church.

There was this

organization called, the Australian Inland Mission, that John Flynn was with.

And they have all these, and just go around. They they just jump station.

so we had a man called

Skipper Partridge who married us and

Kurt Johannsen,

Martyn’s uncle had a nice house in

Alice Springs.

and he said we could get married on his verandah. So I had no one to come of course, but they had about 40 relations and friends coming.

Yeah.

There was no delicatessen, or anything,

and and on his way in, Kurt

shot

four turkeys.

He cooked them the next day in the copper.

My dear Jesse.

No doubt you will be surprised to see.

I am still in Alice Springs, but was married in May and I am now living happily ever afterwards.

Oh, that's Martyn and me on our honeymoon. We were in the mustering camp. Very romantic.

So I am now one of the outback pioneers.

We bought a caravan and so reside in the garden. It is 14 by eight feet with a kitchenette divided off at one end and four foot long.

My father-in-law drove in

one day and said,

“Neutral Junction’s for sale and

it’s empty. And there are no cattle on it. And

we’ll buy it

and

Martyn can go as manager.”

So of course, Martyn was thrilled to bits.

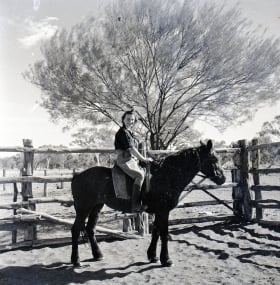

This is my first driving lesson on Mount Swan in the Jeep. It look so English, doesn’t it? Long skirt and a petticoat.

I drove the jeep about ten miles all by myself one day as Martyn was driving another vehicle. I only flattened one little gum tree, but luckily it sprung up again and is still living. All the cattle and sheep cleared off the road as I thundered madly along, and even the rabbits ran for their lives.

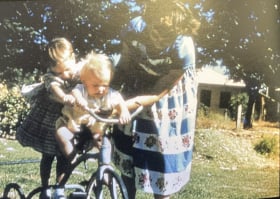

Yes. I had two

children.

Suzette,

she was was born in the Alice Springs Hospital at so was Grant.

This was the John Flynn church

and this was Suzette

when she was christened.

On Sunday we saw a strange sight. At least it was strange to me. A string of three camels walking across the paddock with a couple of black fellows leading them, one carrying an armful of spears and the other holding back a couple of dogs.

They had their worldly possessions on the camels, but looked to me like an array of small shell tins and a fine assortment of much used billycans.

I got a snap of the procession, so hope it turns out well.

Mount Swan Station.

Northern Territory,

October 1952.

I think in 1964, if there was a trained nurse living on the station, or if they employed one, if you had more than 50 Aboriginals -

well before I left there were a hundred -

then

you could build a room, separate from, had to be separate from the homestead with

running water, and they’d come up and inspect it. And then they’d pay the nurse to work part time. And then they’d equip it

Anyone who was sick or cut their hand or anything, they’d come around

and it worked very well.

Apart from the Aboriginal people,

there were

four families living at Neutral Junction.

With the husbands and wives and the children, that made about an extra 20. Of course, we had staff as well.

We ran a road trade business

for cattle. At Barrow Creek, there was the telegraph station

the Barrow Creek Hotel had a staff of about six people usually. So they all came to me if there was any sickness. Well after dark, there were no street lights, so

it was all pitch dark,

and

the cattle would like to stand on the road because the bitumen was warmer at

night time than the

grass. Your headlights would pick up their eyes. But if they weren’t facing you, well you wouldn't see them because

they were all dark cattle. And there were [the] most terrible accidents.

And of course there was

no-one to help them.

Then, if someone went by they’d stop at Barrow Creek post

to tell the people there or wake them up. And then they’d ring me.

There was no doctor.

I had to go

and say the accident and see if it was bad enough, you know, for an ambulance.

But because I was only part time. I had two little children, I couldn’t stay over, you know, at night time. If they needed hospital, they needed hospital.

I took a refresher short hand typing class and

this advertisement came in The Advocate. A cadet journalist for two year training

Wanted at The Advocate. I was 50.

So when I walked in,

So that, it

“Did you not know we advertised for a junior?”

A month later, I think, or a fortnight later… I got a “Ring me if you’re still interested in job”. So I went down and he said,

“The juniors can’t type and spell!”

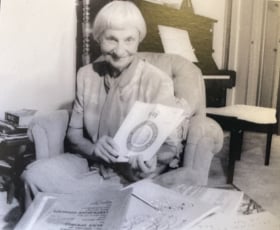

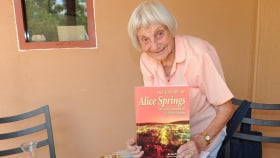

“The History of Alice Springs Through Street Names and Landmarks”.

There are over 600 names in it.

The Petricks had a house in a street called Renner Street. RENNER. And in

the book, he was the doctor for the telegraph line. He had the longest

surgery in the world.

From Port Augusta up to Katherine River.

Oh, so excited!

I had this big envelope saying addressed to me ‘strictly confidential,

private’. I thought, oh it must be a street fine. I've gone through the yellow lights... a street fine. And then when I opened it, it was saying I had been nominated for the O.A.M. for my historical [work] and would I except? So I said of course I would.

This is the Administrator pinning

my badge on. This was at Madigan’s Restaurant.

Shat's the fifth edition of that book. I also wrote a book about the lady

that built a

a pipeline at Hemannsberg.

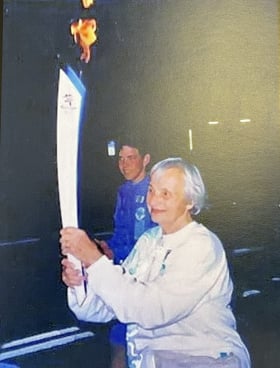

Then the next I had an identical envelope. I thought this is the fine. It went on to say I had been nominated to carry torch at Alice Springs. So I was over the moon. I thought what an

Honour.

When they gave us torches, they said there was a little loop at the bottom. And he said when you light your torch, you must hold that down. But they didn't say you must hold it all the time you’re running. Because that was a little gas cylinder.

So, everyone let it out and then you had to wait until the man

with the little lamp came up and could re-light it. It went all around Ayers Rock

which is five miles so everyone let it out there. I was supposed to start running here at 5 o’clock in the afternoon. We got here at 4:30. And, it didn't come in until 7:00. We were so cold!

I carried it from the gate

and just after he started, this Aboriginal lady came running out of the bush, and she gave me this big bunch of native flowers.

And we all had a well behaved school child as our escort.

And I had this nice young boy of about 14. So I gave him the flowers to hold ‘cause I couldn’t carry the torch.

It was pitch dark. And they’d front lit the Heavitree Gap Gap. It looked beautiful with all the gum branches silhouetted and the rock was glistening with the different sparkles in it.

stepped off the boat from Bournemouth Town. Young Jose with dreams in her eyes. A working holiday took her far and wide beneath the southern skies. But she stayed on. She stayed on in the heart of the red land. Married the boy next door at dawn. Began a life on Neutral Junction sand.

Governess at the McDonald Downs Station, a few hundred clicks from Alice town. Planned just two months beneath the sun. But her heart would never settle down. She stayed on. She stayed on in the heart of the red dust land. Married the boy next door at dawn. Built a life on Neutral Junction sand.