When I lay in bed...

I mean I mean this very seriously.

I actually speak to myself.

I say, “Stop looking backwards.

Look forward”, because

there is no point in looking back

and regretting all those things.

So I say to myself, “Look forward”.

What I really mean is that

get off your backside and go into

the studio tomorrow and do some work.

Look forward, don’t look back.

My name is Guy Warren.

Guy Wilkie Warren

if you want the full name.

I am 101 years old

and I was born in the city of Goulburn

in 1921

I have extraordinary good, like

most old people I think, long term memory.

I can remember being in Goulburn

as a child.

I can remember being in a pram

in the main street of Goulburn.

I had

one, two, three, four...

four or five maiden aunts

and they were maiden

because they never married.

And they never married

because all the young men

in Goulburn

had been killed in the First World War.

And the story I heard was that all

the Goulburn boys were in the boats

that first went into Gallipoli.

Whether that was true or not,

I don't know.

But what I have seen

many times later,

wandering through the bush,

wandering through the country,

driving around.

I used to at one stage often

stop at the local cemetery

in any country town,

and if you do, you find one

name and six people with that same name.

And they were all boys

from the local farm.

And one joined up

and then the next one grew

up a bit and he joined up,

and then six of them joined up.

Appalling.

My mother was born

into a very large family in Goulburn

and when she was born

there was something like eight kids

I think.

I forget the number now,

but I know it was a big family.

And there was measles in the family.

All the other kids had measles

and when the new baby arrived,

obviously they didn't

want to have a new baby in the house

if there was measles there,

so they gave the baby to

an elderly aunt.

What would have been to me a great aunt.

I think.

And they reared her.

They never gave the baby back.

That's Aunty Fanny’s house and that's

the house I was born in, in Goulburn.

That’s my Mum

with a violin in her hand

by the look of it

and that’s her playing piano.

And she was a very good singer.

She learned the piano,

she learned the violin,

and she was good at all those things.

And Dad was a pianist.

So obviously that's how they got together.

Okay, well,

that photograph is of the Empire

Theater in Goulburn

where my old Dad played the piano.

And that's my Dad.

The cinemas in those days, of course, were

like extraordinary theaters.

They were magnificent pieces

of architecture

and razzmatazz.

And he was the pianist and

in the days of

no talkies, when

all the spoken words were written

on the screen in front of you,

there was no sound.

In order

to have music and appropriate music,

there was always a pianist

and usually a small orchestra.

And Dad was such a pianist.

Mum was the violinist.

And I know Dad had,

when Mum could no longer could do it

or had kids to look after,

he had a small group with him.

You don't ask questions to your parents,

which is a great shame.

You don't know the questions to ask,

of course.

But we moved. We never owned a house.

We moved every two years

and we moved to every suburb in Sydney

and in retrospect

I would guess it was because

Dad had a two year contract

with the cinema.

I remember in primary school

being very proud of the fact

that I could point to the flier

which said,

‘Playing at the local cinema was Leonard

Warren and his...’

whatever they were called, and saying,

“That's my Dad!” Big deal.

Poor Dad.

Talkies came in, of course, exactly

in the depths of the Depression.

So he got a double whammy.

He lost

his job because the talkies came in

and it was right

in the depths of the Depression.

Poor devils.

They really struggled after that.

Yeah, we've been lucky.

I've been lucky.

They were tough times.

One in five people were out of work.

My memory of the Depression is of

lines of out of work

blokes on every street

corner in Sydney, particularly musicians

who are the first people to feel

the rigors of

being out of work.

Nobody wants to

pay a musician.

My memory of Sydney is of a muso on

every street corner, busking for a living.

And on the rocks

around the eastern suburbs of Sydney,

I have a clear memory of

out of work fellows

who'd saved a bit of

timber that had washed ashore

on the rocks and had built

huts.

Somehow they must have made them

waterproof.

They certainly couldn't

have made them warm.

I had to leave school at 14 to

earn a little bit of money to help them,

I guess,

although the pay was so poor

that I can’t

believe that it helped them very much.

But I always regret having to

have to leave school at 14.

That was much too early.

And my brother, of course,

who wanted to be a doctor,

never had the chance to do that.

But these things happen.

You know, that's part of living,

part of life, part of the world.

I can remember

when I was 14 and that was in high school.

I was just leaving high school.

Mum always managed to have a Sunday roast.

I don't know how she did,

but I do remember that

half a leg of

lamb was a shilling.

How do I remember that? Somebody...

maybe she or maybe somebody told me that,

but a shilling that's...

well, what's ten cents now.

I can remember

breakfast that my brother and I

had, having gone

for a swim in the morning, and come back.

And there were

big sandwiches of bacon

and a bacon sandwich

and a sunny morning in summer

after a swim.

Man, that’s really living!

It really is.

Why don't I do it now?

I'll have a sandwich tomorrow.

Bacon sandwich tomorrow.

Through somebody who knew somebody

who my parents knew,

I got a job as a proofreader’s

assistant on the old Bulletin newspaper.

It was a weekly newspaper,

and the old Bulletin had a reputation

as being a farmer's country magazine.

The proofreader in those days

was fairly powerful.

He wasn't a journalist.

He was a proofreader,

and he'd checked every proof

for mistakes.

In a funny way,

I probably got a very good education,

at least in English from him,

because I was his assistant

and I had to read out

the journalist's copy

while he checked all the proofs.

So I don't regret that

except that I think I was there too long

and I was fascinated by the journalists

and I liked using words,

so I wanted to be a journalist

and I started writing bits

and pieces for them.

But I was particularly interested

in the fact that

the bulletin

didn't have any resident artists,

but its pages were full of jokes.

All the jokes and all the drawings,

of course, were drawn by

outsiders, by freelance artists.

They weren't done by artists

who were on staff.

There was only one guy on staff,

and he was the guy

who actually collected the drawings

and spoke to the artists.

And I saw these guys coming in

every Thursday

I think it was, with their jokes.

They'd disappear into his room

and the door would close

and there'd be great roars of laughter.

And then they'd come out half an hour

or an hour later

with a little bit of paper in their hand,

and they'd go to the front desk.

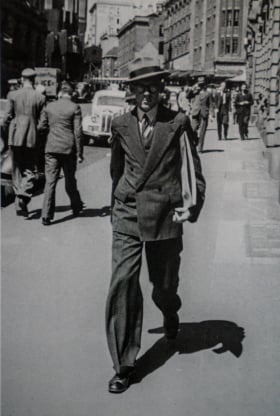

This was at 252 George Street,

and they'd go to the front desk

and swap their bit of paper for a cheque.

Then they'd go out onto George Street,

turn right, and go into the nearest pub,

which was next door.

And I thought, “Gee, you know,

that's a pretty easy life”.

So I thought I ought to be an artist.

I'd always drawn anyway.

I'd always wanted to draw.

So I started bombarding the art editor

with joke

drawings,

and they were obviously very bad.

But bless his heart, he was very kind.

And he didn't do

anything about it.

He didn't

say anything until one day he'd

obviously had a bad day.

He said, “You don't do it like that.

You do it like this!”

And he grabbed my bit of paper

and he took a pencil

and he drew something on the paper.

I can still remember his drawing.

It was a damn sight better than mine.

And then he grabbed me by the arm,

literally grabbed me by the arm,

dragged me out of his office,

up the steps, into the main

office, down the steps,

into George Street.

Up George Street to a little street

on the right, the name of

which I've forgotten.

It was full of old colonial type

buildings.

He went into one about halfway up

the street

and took me upstairs

to about the second floor

of this old building

and threw me through big swing doors

and said to the bloke inside, “Teach

this kid to draw”.

And then the art editor buzzed off

and left me there.

And it was a little private school run

by somebody called J.S. Watkins,

who was a trustee of the Art

Gallery of New South Wales.

He was a painter and a good painter.

It was

a traditional school with a tradition

that goes way back to Leonardo.

It was about seeing

and putting down what you see

and the skills that you need

with which to do that.

It was nothing about

imagination or investigation or

excitement.

It was straightforward

drawing and painting what one sees.

It was a skill.

It was skill oriented.

And I was grateful for it.

And I had a very good basis

in exactly that.

And that meant that I left the Bulletin

because they sacked me when I was 21.

Lousy creatures.

I thought I might have gone on

and become a journalist.

But anyway, they obviously had enough

journalists and they didn't want me.

So at 21 I decided...

things were getting a bit hectic then,

so I decided to join the army.

The Japanese at the time were battering

the door down in Darwin

and, at a moment of patriotism, I decided

I ought to do something about it,

so I joined the army.

But what that meant was,

by the time I went into the Army, I had a

lot of skill in drawing.

Being in the army on the whole

is awfully boring

because you might be frantically busy

sometimes doing all sorts of awful things,

but there are times

when you do absolutely nothing and blokes

sit down and play cards,

which always bored the hell out of me.

But I could draw them playing cards

and I could draw them anyway.

I remember I used to draw all my mates.

In fact, I think at one stage,

in New Guinea, I used to charge them

for drawing them, which

showed a degree of acumen that I

don't seem to have followed since, sadly.

But it was fun.

And by sheer chance,

I didn't get it out for you,

on my table here in front of me,

is an old sketchbook

which has on it

‘Bougainville Sketchbook 1940s’.

And I served for a few years

on the island of Bougainville,

a couple of hours

flying time east of New Guinea.

And these are some of the things that

the War Museum has.

These are

drawings of Japanese

which, bless them, they photographed

and let me have photographs of them,

so I haven't lost them entirely.

They’re in the museum

and I have good photographs of them.

And I still think they’re damn good.

Well, he's obviously not a Japanese.

He was a fellow soldier,

a fellow sergeant.

And that's one of the Japanese.

They’ve all written their names on them.

I asked them to do that.

How I did that, I can't imagine.

I guess by sign language,

but I've had them translated since

and they are indeed proper names,

which intrigues me because in a similar

in an opposite situation,

an Australian prisoner of war

would have written ‘Ned Kelly’.

But these guys wrote their proper name.

They were much more disciplined

than our lot.

Oh I won’t to go through it all.

A lot of landscapes and a lot of a lot

of local indigenous people.

And I was

always intrigued by the way they

decorated themselves,

not only their tribal decorations,

but if you gave them anything,

they would put it in their hair

or in their lap-lap, or they would...

it became somehow a part of their body.

And I quote one particular time

when drawing a big black guy,

and the guys in Bougainville

are very, very, very black,

they're the blackest in the South Pacific,

and I had

I used to pay them with cigarettes

or tobacco or something like that

and I had nothing with which to pay him.

So I went into my tent

and found a tin of talcum powder,

a pretty unlikely thing to have,

but the Comforts Fund had sent up

tins of talcum powder because they thought

it would help skin disease.

I don't think anybody ever used it. But

anyway, I found a tin in my tent,

so I took it out and gave it to him.

He immediately opened it,

poured it into his hand,

and made these wonderful, great marks,

white marks on his big black body.

And I thought, “Wow,

only an artist would do that.

That's great”.

Anyway,

that image has stayed with me ever since.

And there was another related incident

which added to that

which happened... 10, 15 years later.

After I'd

come back to Australia, I did a course

at the National Art School, which was then

called the Sydney Technical College,

and that was an art course.

And then I married

and my wife and I went to London

looking for a job

and I got a job,

and so did she, in those

days and we had a little flat

just out of London.

And this was the early days of television

and we had a little black

and white television set.

And I saw a documentary by some person

who'd been in New Guinea, in the highlands

of New Guinea at Mount Hagen,

where there was an annual...

there was in those days,

an annual dance festival.

And dancers come from all over

the South Pacific, from all the islands,

and they dressed themselves

in the most outrageous clothes.

But all local material.

They used feathers,

plants,

anything you can think of...

mud, anything at all, which become

fancy dress, if you like, dance dress.

And the thought suddenly

occurred to me

that what these guys are doing

is not just dancing,

but by using all this material,

which is local indigenous material,

what they have around them,

what they are really doing

is making a statement

about belonging to their land,

not somebody else's land, their own land.

And I thought, Gee, I'd like to have

some of those photographs.

So I wrote to the BBC and said

something like, “I'm an Australian artist

living in London,

drawing my memories of New Guinea,

painting my memories of New Guinea”.

And whoever got the letter

probably thought, Well, here's an idiot,

you know, who would want

to paint New Guinea from London?

So he may have passed the letter around

for all I know.

Anyway,

about a week later

I got a phone call from somebody and

he said he was from the BBC and he thought

he might be able to help me.

He said he did have some photographs

from the documentary

that I had been looking at,

but he wouldn't sell them to me

as I wanted him to.

He said he'd lend them to me,

but he introduced himself over the phone

and he said his name was David

Attenborough.

And would I like to come around

for a drink?

Well,

David wasn't well known in those days.

He was just a bloke from the BBC

with a name as far as I was concerned.

So my wife and I went around for a drink.

It's odd, isn't it?

The little things that one remembers.

Totally, totally,

utterly insignificant things.

Why the devil should one remember them?

Because we sat down in his lounge room

and he said, “What

would you like to drink?” And my wife said

she'd have a gin and tonic.

And I said, “I'll have a whiskey.”

And so he poured me this small whiskey.

And he said, “What do you like in it?”

Meaning you know, water or soda

or whatever.

And I said, “Well,

actually I prefer it neat”.

And then he looked at me and said, “Oh,

well,

you'd better have more than that”

and he went...

I mean, why should I remember that?

I still keep in touch in touch with David

very occasionally.

And he sent me a note

for my 100th birthday, which

was a great thrill.

Bless him.

Well, springing

from those two connections with land.

First of all, with that

connection

with the fellow in Bougainville.

And secondly,

after talking to and listening to David,

not only when I met him,

but subsequently all his...

all his programs,

and also a better understanding of our own

Aboriginal attitude

towards land, our own Indigenous

people's attitude towards land.

Maybe

it's a romantic idea.

I don't care. I like the idea anyway.

I like the idea of us

belonging to the land,

belonging to the universe,

not owning it, for God's sake.

We don't own it.

We are part of it.

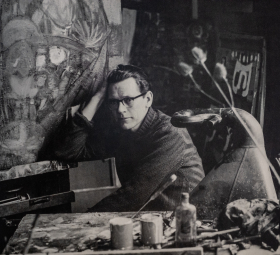

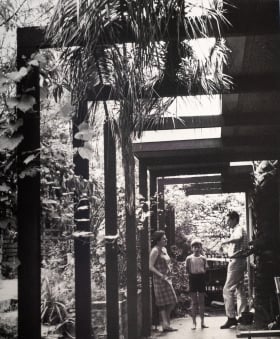

And what I frequently do

is to inhabit my landscapes with figures

which don't necessarily

have to look as though they're

in the

painting to give it scale

or to give it interest.

But looking as though they're

as real and as insignificant

as a tree beside them,

as though they're part of

whatever it is they're in.

If you're in a thick rainforest,

you are there and that's it.

It does take over you. You are part of it.

And the vines, the lianas, that

wind their way through it and around

you and everywhere.

You're captured by it.

You are part of it.

Anyway, it's like

the lianas are like

three dimensional

drawings,

just weaving through space.

Look, I don't...

I'm not dogmatic.

One of the

great American painters

whom I respect enormously

said, among other intelligent things

he said,

“Art can contain anything, anything at all

except dogma of any kind”.

So I don't want to be dogmatic,

and I do do other things.

I don't always follow my own rule.

There are no rules to this crazy game.

It's about expression.

One should be able to...

An artist needs to be

curious.

We all need to be curious.

We ought to ask questions.

Is there a better way of doing this?

Why can't I do it this way?

Who says I can't do it that way?

One should be

capable of

doing,

painting anything one wants to.