You might be one of

Australia's oldest

uses of the computer, actually,

if not the oldest.

What do you use your computer for?

Nothing special.

Just normally use it

for contacting people

or looking up bank accounts,

all that sort of thing., General purpose.

It's a general purpose.

Probably 101st.

That’s 105th birthday.

My name is Colin Lens Wagner.

And I was born in Adelaide,

December 2nd, 1917.

In those years,

the parents named their children

after a battle of World War One.

So I was called Lens.

L-E-N-S. .

Colin Lens Wagner.

My parents were very hard working.

They had a shop

and they had a machine shop

and they had a bicycle shop.

His name was William Wagner

and he tried everything to make money.

He was a hard worker.

Well you see, after the First World War,

when the soldiers came back,

they had brought a broader sensitivity,

get things done.

I had two sisters.

I got on alright with them.

They were about ten years old than me.

I was a late one starter.

But,

one was a wild one

and she was an icon of the Roaring 20s.

She drove

my parents up the wall

with all those carryings on.

I do remember the

opening of Canberra in 1927.

I have an official invitation to there,

to the opening of parliament house.

My parents took me there in a car,

in a 1925 Studebaker.

It was very difficult.

We had to go through the Coorong.

The Coorong didn't have any

roads properly then.

Just track.

Down to Mount Gambia

and across the mountain range to

Canberra.

There couldn’t have been too many camping

in Canberra, in the caravan park,

because one water tap did everybody.

Did the lot.

The tap was frozen over

until about 9:00 in the morning,

so they must have been cold nights.

And all the supplies

we had to get were from Queanbeyan.

There was nothing open in Canberra

They were still building it.

They were getting

official buildings done.

Parliament House,

they just got that done in time.

My parents,

I remember, them

saying to me, we’re taking you so you’ll

remember to tell it in years to come.

And here I am telling

it in years to come.

I remember the opening.

All the guards were there

for the opening, in three rows.

And one of them feinted

and nobody knew

anything about it for a while

until they got him out of it.

So I guess they were

World War I soldiers

being re-used again.

Three planes flew overhead.

I heard one of them crashed

and the pilot was killed.

My father took me to see

the wreckage of the plane.

It looked,

quite simple.

Nothing much of it.

It was enough to kill somebody.

Twin winged planes.

I just remember those little bits

about it.

This radio was built

in 1924 for my father.

It was his first wireless set

and I’ve still got it.

And it still works.

And it was from this set

that I became interested in radios.

That's a crystal detector for it.

And these are coils so you

can get different stations.

It's quite a primitive set

but there's two valves.

You can see the valves in there.

They amplify the signals that come in.

It’s from there

that I made my own radio sets.

I reckon about eight or nine

years of age.

And I got books from,

you know, magazines from England.

And they had crystal sets.

The boys magazines in England.

And I made a crystal set

and I made a one valve set

and a two valve set. All shortwave.

And I'd be in my room

with earphones on until about one

or two o’clock in the morning

listening to overseas stations.

And I think it cost them 15 pound.

It was a hell of a lot of money.

Price of a push bike.

My father had a shop down on

Glen Osmond Rd.

It was close to Parkside

and it had a big garage door on the front

which he opened up

and there was a radio in it

- a seven valve all wave super heterodyne

with a big speaker on it.

And a lot of people

used to come along with their chairs

and listen to the radio

until about 2:00 in the morning.

That was the cricket in England

that they would listen to. Parkside.

This was during the Depression.

But the interesting part

about that radio, it was made by me.

And I was about 14 at the time.

The day I turned 16,

I went into the Register of Motor Vehicles

and got a license to

ride a car or drive a motor vehicle.

And my parents gave me a motorbike.

A secondhand one.

And I rode it to school

and all my school mates

were looking at the beautiful chrome tank.

They thought how lovely it was.

But the headmaster had other ideas.

He was from the horse and buggy stage

and he told me never to bring it

near the school again.

That was the end of that.

I didn't.

During that bit

between the Great Depression

and the start of World War II,

I wanted a sports car,

and they were unobtainable.

So the only thing to do

was for me to make one.

Which I did.

I made a sports car.

With a lot of help from professionals.

It would have been cheaper

if my parents had gone and bought me one.

If they could have.

Four us

sort of come together

because very, very few

people had motor cars,

particularly young kids.

It was very rare to have a sports car.

And we sort of found one another

and the four of us made friends.

And we all joined the Army together.

Saw it coming.

We reckon, we go to them

before they came and got us.

That’s about what it amounted to.

We joined the Army signals.

there was vacancies for signalers.

And we just went in

part time until 1939.

And then when the war started,

we went in full time.

One was killed in the Middle East

with a bomb.

The second one died as a P.O.W.

in Singapore.

And Steve Tillet,

he picked up a bullet in New Guinea

and he was flown back to Australia

more dead than alive

but he survived and he got better again.

So really two of us survived.

Just luck.

You’ve either got it or you haven't got it.

Yes, I was sent

to Woodside Military Camp.

And from there I was sent to Loveday.

I had a good background of radio.

Knew all about it.

They wanted to establish a radio link

between Darwin and Adelaide.

And I did.

Then I rigged up another aerial

to see if I could get Adelaide, and I did.

So we

we had a very precarious radio link

between Darwin and Adelaide.

And they said, “From now

on, you’re an instructor”.

I said, “I don't know

anything about instructing”.

They said,

“Well you’ve got three stripes,

go out and earn them.”

So that was the end of that.

When you're in the Army,

you just walk along a tightrope

and you don't fall off.

You do exactly what they tell you to do.

So that was 8:00 in the morning.

And I said,

“Can I have four hours leave?”

And they said, “Yes,

you have leave till 12:00”.

And I raced around and got my

future-to-be wife.

She was from Menindie,

up on the Darling River.

Yeah, well I met her because

I was one of the very,

very few young kids who had a motor car.

We were fair game.

I said, “Shall we get married,

we’ve got four hours to do it?”

[Before] I get back to camp.

So in those four hours we

went and got married

and I got back to camp.

And then I went off to Bonegilla to

establish the Number One Signal Training.

I did it if for about 12 or 18 months.

because of my qualifications

being an instructor,

I was sent to the

signal office in Townsville.

And it was run by girls, about 15.

AWAS they were.

Australian Women’s Army Service.

They were all good.

I had ten days leave

I came home in that ten days.

I bought a house at St Georges

and that provided Peggy with

a roof over her head.

Yes, I joined a unit then.

An operational unit.

The 2/3rd Anti-aircraft Regiment.

And we were attached to the 9th Division.

We were classed as a

defensive unit, not an offensive unit.

An offensive unit is infantry.

You go out looking for trouble.

A defensive unit is us.

Let trouble come to us.

We were supplying all the communications.

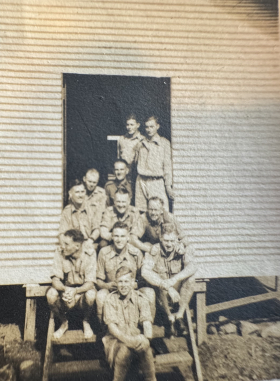

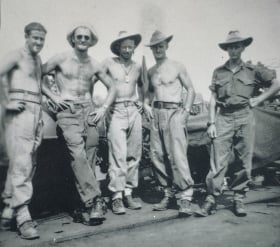

We headed [off] on a troop ship.

There was about 2,000 on it.

We played chess all the way to Morotai.

It was very hot.

We were just with

no shirts on.

I took some photos

of being on board

the ship along the way to

Borneo.

And then another chap took our photo,

just myself and the four drivers.

Now that’s a photo of us on the LST.

Just before we did the

the landing.

That's me.

That's our four drivers.

He said, “I want to take your photo.”

So we found out after.

He said, “I took your photo

just it case you didn’t make it

on the landing.”

But we did.

There wasn't any harbour there.

To get off the boat,

they threw rope

ladders over the side of the boat.

We saw some LSTs or ‘Landing Ship Tanks’

coming in.

Ready to come in one at a time

and we knew they’d be for us.

Rope ladders over the side,

we got on the boats.

But the LSTs,

all went in.

We unloaded

and there’s a photograph of me

coming off.

It must’ve been pretty late

because we couldn't get off the beach

and we just held the landing that night.

We expected

air raids or something

but it never happened.

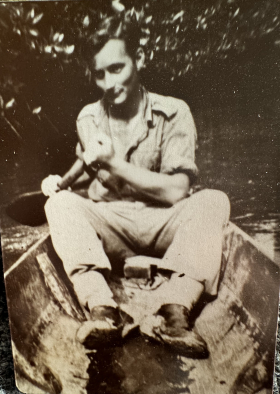

I had a cheap camera with me.

If I’d had an expensive one

it would have got pinched.

I had a cheap one

and another chap in the unit also

had a cheap one.

Similar cameras

and he knew more than I did

about developing films.

And he said, well,

if you go to the up to the RAAF,

their reconnaissance unit,

that's the ones that take photographs from the air.

Air photographs.

He said they've got some material.

Here's what to get.

And he said it'll take

at least 30 cigarettes to get them.

I received a cigarette ration

and that gave me cigarettes,

which were very handy to me.

Ten cigarettes I used to buy an egg with,

but the rest I used to get photography with.

So it went over

with a handful of cigarettes

and put them down on the table.

I got it

and we came back

and we developed the films at night time.

It had to be completely dark

and we made a torch

with a red rag over it

to see what we were doing.

If anybody had turned a light on

at the wrong time,

we would have lost everything.

But they didn’t.

And we developed films.

You know, a 'jungle developing

company’ sort of thing.

And got away with it.

We did it.

And it was at that point there

I thought the war would never end.

I’d been in it for six years

and the war was just going on and on.

And then

the atom bomb dropped and

war suddenly came to an end.

I found out on the grape vine.

Yeah I was just pleased that I’d made it.

But then, of course, came the big thing,

the surrender.

We'd found out that there was a death march

2000 Australians were murdered,

and we wanted to round up

the people who did it.

And we did.

Sandakan was not far away

from where we were at Labuan.

And that was where the death

marches started from.

Most of the garrison from Sandakan

had gone inland to Ranau.

They murdered them along the way.

Someone had to go and pick up

the remnants,

what was left of the garrison,

at Sandakan.

We sent an LST,

a Landing Ship Tank, over.

And one of our group, a corporal -

he was a very good corporal -

I gave him my gun.

It was a machine gun.

I said, “If you use it, clean it”.

They pulled into the harbour

at Sandakan.

The Japanese,

they were all on the wharf waiting.

There was half a dozen wooden boxes.

They were quite heavy.

About the size

you could lift one up

and put on your shoulder and carry along.

They had Yokohama Specie

Bank written on them.

We knew they were full of money.

So the corporal went in and

saw this Japanese chap in the tent.

He was sitting at a table,

the boxes along side of him,

and he was waiting to be greeted

by the corporal.

The corporal walked in the tent,

pointed a gun at him and said,

“Get out and join the others!”

And they were all put on the boat.

On the way back,

they were put in [the] charge

of a private

and the private had other ideas.

He told them to put their packs on

and they put their packs on

and he formed them into a ring

and he made them run at the double

around and around the ring in the heat.

I don't know how long it went on for,

but an officer came down,

saw it and stopped it.

So that was

as close as they got to a death march.

It wasn't very much at all.

They arrived at the back of Labuan

and I was there with my camera.

I took a photograph

on the deck of the ship.

Another couple of photographs of them

walking along.

They were very obedient.

They didn't play up at all.

We opened the boxes.

It was Japanese invasion money

and as the Japanese had lost,

the money was worthless.

The boys made a big pile of them.

I must have had an honest face

because I was given the job

of burning it.

I had to get a long stick

and it was like burning phonebooks.

And the next morning

it was just a pile of red ashes.

A few years ago,

I looked on the computer,

and I saw the 9th Division

had given their version of the surrender.

And it was whitewashed.

It was never correct.

So I was speaking at a meeting

and I gave the real version.

The Canberra War Memorial checked on me.

They said yours was different from ours.

Can you prove it?

I said, “Yes I can.”

So I had photos to prove it.

So here is the real story

of the surrender.

Baba. General Baba.

B-A-B-A.

He was a war criminal

and we wanted him dealt with.

I was standing there

and I saw the plane come over the top.

I was very pleased to see it

and it landed.

I was there with my camera.

But there was an official

camera standing by.

I just thought what a bugger he was.

I couldn't...

you know, there's not much you could do

[as an] individual.

You just.

You just look at them as...

You just don't like them.

General Baba was told to come on a plane

and sign a surrender document.

And they had to put white crosses

over the red rondelles

so we’d know what plane it was.

But to me that was not the case,

the white crosses were to humiliate him.

That was first sign of humiliation.

And it was one of our jeeps

that took the general

to the surrender point.

I was told

he was told to get in the jeep.

Standing alongside him was a big chap,

with 'MP’ on the side...

He was a private.

The general being a general [would] naturally

sat in the front seat of the car.

The private told him to

go get in the back.

This is the unofficial version that I'm giving.

And you can see the

private sat in the front seat.

And you can see

it's real

because the general

is sitting in the back seat.

I spoke to the driver afterwards.

I never used that particular driver.

He said he took him as fast

as he could over every bump he could.

The next two photos

of the general going into the hut

to sign the surrender document.

What our side,

I did,

was to put a mortar gun

right alongside of the hut.

Hard up against it.

And he wasn’t to know about it.

So they marched him in there

and the next photo is taken officially.

You see him signing a surrender document,

and as he signed it,

about to put the pen down,

a signal was given at the door

and the gun went off and

the hut shook very badly.

And I think it didn't do him

any good at all.

A couple of hours later I saw him again.

He was in a hut.

Ordinary tent.

Usual furniture -

a long table and two long chairs.

He was sitting on a form

with his back to me

and there were two lieutenants

standing each side of him.

Each of them had a foot up on the

form alongside of him

and one was pointing his finger at him

and he was saying to him,

“Who told you to lock up civilians?”

And I saw the general just...

He was still in a state of shell shock.

He didn't know...

After that,

they put him into a compound.

The compound the Japanese made.

I saw two or three of them.

They were just four posts in the ground.

Probably about three meters by three meters.

Wire netting up the side,

and

they put our troops in them overnight.

What he was finding out

first hand, what it was like,

he was put in one.

It was all unofficial.

If it rained, he got wet.

All the mosquitoes

bothered him all night.

He wanted to commit suicide,

but we wouldn't let him.

We put a guard there

on a hut.

Guard him all over night.

We put two lights on the thing

to watch him

to make sure he didn't commit suicide.

I had to be very careful

because there were a couple of shots

I would have liked to have got,

but I wasn't game to take.

That would have been the

the general sitting in

in the pen.

I'd love to have taken the photograph

but I just wasn’t game.

I thought I might...

I’d better not.

He survived to be tried and he was hung,

but that that was not my story.

That's someone else’s.

It was the plane

that General Baba came in.

It was sitting there doing,

you know, surplus sort of thing

and a few of the RAAF boys,

air pilots, were basically

waiting for us to get back to Australia

on leave.

So they filled a plane up with pilots

and they flew it back to Australia.

That's how they got home.

It's all unofficial.

And they left it on an airstrip

and forgot about it.

A few years ago,

the Australian War Memorial

in Canberra found the plane,

and somehow or other

they got it back to Canberra.

Probably by road of course.

And they’re restoring it.

It's going to be an exhibit.

We had to wait [for]

a ship to bring us in.

We waited and waited and waited.

We were very frustrated.

And we waited right down to December

the 10th, 1945.

At that stage

I'd walked over to the airstrip

with a handful of cigarettes

to get some more material

to do some more photos.

I heard the engine of a plane start up,

then rev up.

I heard it go down the runway

and I heard the engines suddenly stop

and there was an enormous bang.

The plane had crashed.

Of course we all raced out

and the plane had gone into a ditch.

Everybody on board was killed instantly.

But they seemed to be lying around

just on the side of the plane.

It was that intense.

In about 20 minutes they were all ashes.

You couldn't tell who they were.

But I photographed it.

At that moment,

one of our chaps

from the main unit came in.

He said, “Come back straight away.

Two ships are coming to take us home!”

It was at that point of my war career,

that I had a tragedy on one side and

I had good news on the other.

I felt for the people

who were going to receive

some bad news in Australia,

and I just received good news.

I went down, two Victory ships

had come in, to take us home.

I thought it might be a change of ration,

but it was worse.

There was no...

they were just cargo ships.

1,500 of us

got onto each ship,

and we...

There was nowhere to eat,

nowhere to sleep. We couldn't care less.

We were going home.

And it was wonderful to

go down the Brisbane River.

We thought after two months,

2 or 3 months

after the war,

Australia would have forgotten about us,

but they hadn’t.

It was the 9th division coming home.

The last one.

As we went past the ships in the river,

they fired their fire hoses into the air

welcoming us home.

There was a troop train

standing by

to take us home,

but the people of Brisbane

had other ideas for us.

They loaded us into trucks

and they drove us slowly down

the main street of Brisbane

to a ticker tape welcome home.

I felt little bits of paper

falling on me.

We were wet from a shower of rain.

We were dirty.

We were hungry.

But we didn't care.

We were going home.

And my next thing is

I got

the best Christmas present

I ever got in my life.

It was half past ten

Christmas morning,

1945,

when a train pulled

into Adelaide Railway Station

and I was on it.

My father picked me up

and brought me home.

It was a wonderful feeling

to walk up to my front door

knowing I would

never have to go away again.