Closed captioned icon

View audio transcription

Of a night time, my only prayer is “thank you”. As I’m going to sleep, I say “thank you”.

My name is Hillary Josephine Jose.

I was born on the 22nd of the fifth, 1923,

at the Royal Women's Hospital in Lonsdale Street.

I was

an illegitimate

child.

Well, very basically,

it must have been a one night stand.

Nobody knew who the father was.

it was suggested he was an officer in either the British Navy or the Merchant Navy.

They also felt that the father would had no idea of my existence.

As somebody said once, “It's all over Rover, but I enjoyed it. Now I have a child.” Well, to me, that's very flippant because you have a child.

A child has got to be nurtured, educated, nurtured. You know, it's a big thing.

My mother had arrived in Australia

only

a matter of days

before I was born.

Unmarried mothers,

like

my mother,

would go and work in the laundry

at the Abbotsford Convent.

They would

supply babies such as myself

to the

Broadmeadows Foundling Home.

The legalities,

there were fairly weak,

and there was

very little, if any, paperwork.

I, found I.

I can't remember

going there and there a lots of shoulder

there was a seesaw.

It was, it was, that

I think I might call that a rock. I don't know, but it's. You should go like this.

A couple came in and they'd been to see the parish priest

at

in Brigid’s

in North Fitzroy.

And this couple,

the name was Benn,

Australian wife and a

Chinese husband.

I can remember the parish priest’s name was Father Parker and Father Parker said he approved of the couple taking me as their child but there's there's no paperwork anywhere.

My earliest

memories

would be

holiday

with another family

down in

Aspendale.

And in those days,

Aspendale

was

quite a country area.

I was thinking one day about all the different things that happened to me at school.

And I can remember to this day,

one of the little girls came up and said to me.

I'm not allowed to play with you anymore.

And I remember sort of thinking, I don't know what she’s talking about but I said, “Why?” and she said, “My mummy and daddy said I can't play with you anymore. You're illegitimate.”

‘Illegitimacy’, just the word, spelt out, “Be careful. Look after your children. There's an illegitimate child over there.

Don't let them play with her

The illegitimate child was the lowest at the social scale.

Being brought up a very strict Roman Catholic, in those days... No way known, no way know was there anything foregiven. You're illegitimate, and that’s until the day you die.

Nothing was discussed.

At 18, I had no idea how children were made or born. Or animals.

I had no idea of their conception at all. And I can remember staying on a friend’s farm and the two dogs were having a lovely time outside.

I went inside and I said, “Oh, Bonnie and Clyde”, we’ll call them that,

“are playing. Come and see.” And of course, they were procreating. Is that

Nothing intimate. No. No sex.

I didn't even know the word.

And they used to be a saying:

‘See no evil, hear no evil’.

And they felt

that these

people like myself,

they were evil. You couldn't talk about them because you didn’t know how it all began with them.

I was in junior

in G. J. Coles

cash office

in middle of Bourke street opposite Myer in Melbourne.

I got into the Air Force at the age of 18

and I was mustered as an office orderly.

I got some forms to fill in.

When I took the forms back,

the officer said to me,

“This is all wrong.

This doesn't

make sense.”

He said, “First and foremost,

you

present yourself

as Hillary Josephine Benn.

Your birth certificate

says

you are Hillary Josephine Fraser.

Your name is Fraser. Your original birth name is Fraser.

My boss in the Air Force said to me,

“Now first of all, I want to tell you this. You're not a bad person”. And I said, “how do you know?”

I told him my story and he was wonderful.

And he said, “Well, why do you believe this?” I said, “because so-and-so told me!” And he said, “Well, so-and-so was wrong.”

When I went into the Air Force,

we had to be civilians and then change our lives.

Two different worlds.

They’re just entirely different and you speak

a different language.

The service language.

It was a big, big learning curve

and for some it was quite disastrous. For me, it was the best time of my life.

The Visual Training

Section

Visual education

was introduced

in the

Air Force

because

we were lacking

books;

we were lacking

tutors.

Time was of the essence. It was. There just wasn't the time.

So you may made a film and presented that to 30 recruits,

30 people's attention. They all were listening to the same story.

This officer that had asked me to come into the unit. He took me in hand because I had no preconceived ideas.

I really didn't know anything about

filmmaking.

And

taught

me

the basic

rules

of

photography.

Observation. Very, very important thing. No matter where you are. It wouldn’t matter what you were doing. Be conscious to observe and to listen. You may hear, but you may not listen. It is very important to listen.

Each time he’d teach me something new, he would explain why this is what we want. This is what we want the troops to see.

Try and get get them all on the same wavelength.

And very quickly I became passionate about visual education because I understood the logic of it.

I could see the logic so therefore I could understand it.

Well, you name it, we did it. Like we would make little short films about something interesting but also linked with what

the students were supposedly studying at the time.

There was one

film we made and it was just the

horizon as the aircraft came off the ground.

Okay, your funeral.

Wasted lives. Wasted equipment. Just because he went down for a look see.

Let us now examine some new equipment, which has made possible a delightfully easy method of descent through cloud.

You got out of it what you put into it. There were times that were very sad in the fact that I remember this thing, a training unit, and

we had all been working together in the morning and lunchtime came,

and one of the boys that had had lunch with us,

came back to the table and he said, “Sean's gone down”.

That’s all he had to say, “Sean's gone down”.

Sean was eating his lunch like we all were but it was his time to take his pupil up straight after lunch. And the, pardon me, the plane stalled and it just went boom.

If the civilian people had've known how many training accidents happened, they would be absolutely horrified.

I said to the boy that asked me to marry him,

“I don’t think it's good that you should marry somebody that's illegitimate”.

He said to me,

What did you say?” And I said,

“People say, anybody that’s illegitimate is not a nice person”. He said,

“I didn't ask that person to marry me. I asked you. I don’t know who the other person in your mind is, but I only asked you.”

It made no difference and he was a little bit older, a little bit wiser.

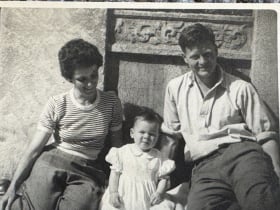

Six months before the war finished, Don and I

were engaged and when the war finished, I was demobbed back to civilian life and

30th of April, Don and

I were married, so that was in ‘46

and

we went to live in a

one bedroom flat

In Caroline Street in South Yarra. And then

we bought a home. But in those days,

if you were renting the home I owned,

and I wanted to go and live there,

the government say “No. You you have to wait.” Well, we waited two years before we were able to go and live in the home that we had bought.

We wanted four children.

I had Anne,

David, Andrew and Jan.

This was something my doctor said to me once. “Hillary,

let Anne play in the garden”, because apparently I was scrupulously clean.

So he taught me how to allow a child to be a child. Not be a little doll.

Somebody asked me what would happen

if my

children were lesbians and homosexuals or all these different things?

Or drug addicts, anything like that?

How would you feel about it?

And I’d say,

“How should I feel? They are my children. You know, that's it. Full stop.”

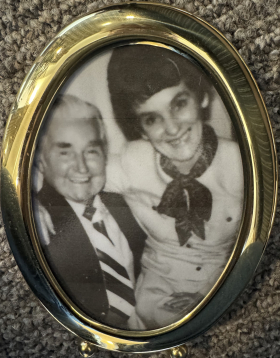

Don died of a coronary.

Along came another lad. By then he was a man in his

late 50s.

And he

said to me, would I marry him?

And I went through this long tale again. Very similar. I can't remember word for word

but he said, “No, no, that's not what I'm asking you. Will you marry me? What are you talking about?” So both of the boys - one was a young man and the other one was a middle aged man - both of them had the same reaction.

Both of them were very decent. They were gentle men as far as a wife was concerned.

When you're married, you love each other.

You're ‘in love’.

If I'm in love with somebody,

to me it's a sexual thing as well.

Whereas ‘loving’ is my friends. But ‘in love’ is my husband.

Life is so interesting. But I think to me I think, what is life all about? I’m dashed if I can work it out, but then do I really want to know? I don’t think so. I just go on in my own odd way and not leave too many tragedies behind me, that are of my making.

Don't worry about what you didn’t have. And don't worry about what you mightn’t have. But just today. Now. This very minute. Don't worry about what you may have been or what might be. No. The now. The now.

It's a pity you know that we don't know some of these things when we start off.

Thanks To

Anne Scerri

Hilary Jose

"It's a pity we don't know some of these things when we start off"

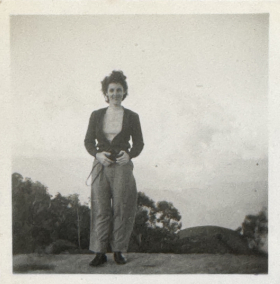

From “Illegitimate” Child to WWII Air Force Trailblazer

Hilary’s story began in Melbourne, born to unwed parents and placed in the Broadmeadows Foundling Home as a baby. Growing up labeled “illegitimate” brought immense challenges and stigma, but Hilary’s strength and the support of her loved ones helped her build a remarkable life. During World War II, she joined the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF), where she learned to operate a film camera and became a camera operator in the Visual Training Section of the RAAF.

Age in Video

101 yearsDate of Birth

22nd May 1923Place of Birth

Melbourne, Victoria, AustraliaThanks To

Anne Scerri